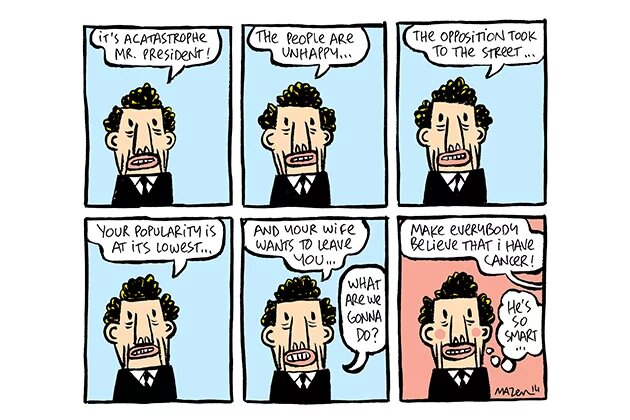

Before 2011, the most common charge levelled against the political opposition and activists in Syria was, ‘spreading false information to weaken the resolve of the nation.’ However, after this “nation” rose up in March 2011 the fabrication of news items and information, and the dissemination of rumour became official state policy. In his speech at Damascus University in June 2011, Bashar al-Assad praised the Syrian media for its contribution to what he termed “an information war”, and praised the supportive role of the Syrian Electronic Army. This was the first official mention of this group of hackers who specialise in attacking media perceived as hostile to the Syrian regime by hacking into their social media accounts and spreading fabricated news. Alongside this, the mainstream Syrian media, in the form of official, semi-official and government-allied channels, continues to broadcast dozens of weekly programmes, which claim to counter ‘media misinformation’. These have gone as far as the absurd claim that opposition demonstrations have been ‘fabricated’ in studios in Qatar. Official television channels have also broadcast the forced confessions of dozens of activists who have ‘admitted’ to falsifying reports and disseminating misinformation and spreading rumours. [i]

The state’s policy of misleading public opinion has infected certain activists and opposition groups in the form of what some termed ‘positive rumours’. These are rumours designed to strengthen the resolve of the ‘nation,’ which the regime is trying to break. As such rumour has become one of the most important weapons in the Syrian conflict – and this is why Dawlaty decided to take on the difficult task of ‘rumour control’.

Eyewitness

Fear and curiosity are fundamental components of all conflict situations and often lead people to invent and repeat information of dubious veracity. In many regards, Syria has been an ideal environment for the fabrication of such information and the spreading of rumours, which in turn have come to play a prominent role in intensifying the conflict and propagating a discourse of hatred and extremism. The war, which has severed lines of communication between residents of different regions as well as between those within each region, has made it even more difficult to check the veracity of such (mis)information. Verifying any given rumour is thus almost impossible in most cases, especially when coupled with the inability of people to move freely (due to sieges and the general security situation), the absence of electricity, the internet, and wireless and non-wireless communications in the majority of Syria’s regions. All this serves to inflate the impact of rumour on the sectarian, regional, and economic levels, not to mention its impact on the daily lives of Syrians, exacerbating an already unsafe, fearful and mistrustful atmosphere, which in turn facilitates the further spread and credulous reception of rumour.

As events picked up pace, some activists fell into the trap of broadcasting rumours or lending them credibility by passing them on before checking them. Other Syrian activists and organizations perceived the dangers inherent in such an approach, leading to a number of initiatives to create ways of checking the veracity of these rumours. Most of these initiatives used social media platforms, such as the Akhbar Shebab Sourya (Syrian Youth News) group—out of which grew Tahrir Soury (Syrian Edit)—and Shahid Ayan (Eyewitness). Among others, these groups attempt to verify or disprove reports using eyewitness accounts, pictures and video footage. A quick review of the work of any one of these groups shows the extent to which reports have been faked and how images, footage and events from other countries (both regional and international) are recycled, as well as the number of parties attributing different contexts and dates to identical reports.

Fact checking and fighting rumour

Based on the above, we at Dawlaty decided that it was imperative to counter the spread of rumour in Syria by training activists to check reports, verify information and so strengthen their role in fighting the creation and dissemination of false reports. To this end we developed an online application form to select participants for our workshops. In this form we asked applicants to describe some of the rumours they have had to deal with, their descriptions gave us further insight into the rumours circulating in Syria. This information allowed us to identify fundamental differences between those regions under the control of the Syrian regime, areas controlled by the opposition, and those dominated by extremist groups linked to or affiliated with al-Qaeda. These differences manifest themselves in the form and type of rumours, and the manner in which they were disseminated. There was, for example, a clear difference between the type and source of rumours that influenced activists in the southern and central regions and those that influenced activists in the north.

The majority of the rumours that southern and central activists spoke of dated from between 2011 and 2013, and came from different sides of the conflict. Rumours originating from the regime tended to promote sectarianism and regionalism, for example, the rumours of sectarian clashes between the al-Sabaa and al-Nozha neighbourhoods in Homs in 2011, which claimed that individuals from both areas were killing each other along sectarian lines—not on their own initiative, but as part of a coordinated strategy to wipe out the other neighbourhood. Since the early days of the peaceful revolution, the regime has spread rumours about “terrorists” targeting electricity stations, cutting supply lines and exploding oil pipelines to justify the bad economic situation in the areas under its control.

Rumours from the opposition, such as the regime poisoning drinking water, gained currency in various regions throughout Syria, particularly in Deraa, the Damascus countryside and Deir ez-Zor. Other rumours which were still current at the time of the workshop were mentioned. These rumours dealt with Syria as a whole, such as the Syrian regime’s ‘intention’ to issue new identity cards only to residents in regime-controlled areas, and that all those who did not obtain these documents would be barred from holding Syrian nationality.

Most of the rumours discussed by activists from northern Syria were of comparatively recent date, either— current or from only three or four months before the start of the workshop—and almost all of them were about ISIS (The Islamic State in Iraq and the Syria). Some of these rumours originated with ISIS itself, while others focused on where ISIS would be, for example ISIS returning to areas from which it had previously withdrawn, such as the countryside west of Aleppo. Activists mentioned the direct impact such rumours had on residents in these areas. ISIS systematically used rumours to discredit its opponents and to justify its actions towards them. For example, when ISIS was aiming for total control of Raqqa, it bought the loyalty of some armed groups and tribes, spread rumours to discredit those who refused to join it, eventually managing to defeat them and push them out of Raqqa.

On the basis of this survey we decided to hold two workshops, the first during December 2013 in Lebanon for activists in regime-controlled areas as well as some Syrian activists in Lebanon, and the second in Turkey in April 2014 for activists from opposition or extremist held areas. Holding two separate workshops allowed issues to emerge that might not have arisen had we gathered all the activists from the different areas in a single workshop.

“Positive” rumours

There is confusion over the concept and definition of rumour, and a failure to appreciate its destructive consequences. At the beginning of both workshops there were definite uncertainties about what qualified as a rumour and what might be categorized as a strategy that was permissible to use in times of war or conflict. At both events, some activists made early references to what they termed “positive rumour”, by which they meant a rumour with the aim of achieving a “legitimate” objective, such as mobilizing people to protest against the regime, mobilizing public opinion around events in Syria, or protecting a given area from military assault. Initially the workshop participants insisted on the value of deploying such rumours in Syria, especially during the period of non-violent revolution, when their use, they claimed, played a vital part in winning support to stand up to the armed and violent regime, then later in ISIS-controlled, or formerly ISIS-controlled areas, as part of what they regarded as ‘legitimate wartime strategies’. Much of the discussion in the workshops was dedicated to participants describing the direct and indirect (often imperceptible and unacknowledged in the short-term) impact of these rumours. In light of these discussions, the majority of those who had formerly insisted on the need to use rumour in times of conflict eventually changed their minds. In addition, it emerged that the principles on which the revolution was based, or rather the ethical values that activists of the protest movement espoused, were not as fixed as they had initially appeared, and at times even came to resemble the ‘morality’ of the Syrian regime. All this has weakened the uprising’s credibility in Syria. Alongside this there has been the impact of the activists in the non-violent movement and the political opposition’s use of rumour on world opinion through those international organizations tasked with documenting human rights violations, which were initially reliant on local sources to forward reports of violations in targeted areas. This was particularly so after the start of the revolution, as it was then even more difficult for journalists to enter Syria or for the UN to move about freely. This increased the dependence on local activists as sources of information for international organizations, most of whom were untrained, or had little or no prior media experience. When these activists reported on incidents that had not actually taken place or exaggerated those that did, they lost credibility. On numerous occasions this lead to the international organizations, who had relied on the activists, finding themselves embarrassed following the publication of a given report, which was later completely disproved or turned out to be based on inflated figures. One example of this is the ‘massacre’ in the neighbourhood of Khalediya in Homs where reports were published of the regime killing more than four hundred civilians, only for it to become clear that the corpses shown belonged to regime and Free Army fighters who had died during direct combat in the district. Yet at the same time the regime was indeed perpetrating mass murder against the civilian population, and there had been no need to indulge in exaggeration or present anything other than the truth. Even more tragic was that in the wake of the rumoured al-Khalediya massacre, ‘revolutionary’ regions throughout Syria showed their solidarity by taking to the streets to demonstrate against the regime’s actions, leading to many activists being detained by the regime’s forces - not as a result of real events but of a fabrication, which further weakened the position of revolutionaries.

At the beginning of the second workshop, some of the groups produced shocking instances of participants’ direct involvement in rumours which had resulted in the deaths of many civilians and soldiers. This highlighted the many-layered risks of using rumour, and had a direct impact on changing participant’s perceptions of the value of “positive rumour”. After conducting the two workshops on rumour control we are continuing to work with the participants who are now applying what they have learned and reflecting back on it. Given the somewhat vague nature of the concept, a core point was that participants develop a working definition of what ‘rumour’ actually is. This is what they came up with:

“A specialized intelligence tool, usually carefully researched, and containing a great many details, thus rendering it difficult to detect. Rumour differs from propaganda, in that it involves false information, exaggeration or the addition of false details, with the aim of creating a certain approach to, or coverage of, a given incident, or entrenching a given state of affairs, and it is then deployed as a part of propaganda. Propaganda is a comprehensive methodology used to shape a future set of affairs or to deny or entrench current circumstance. Rumour is used to emphasize certain details.”

The workshops included opportunities for participants to discuss different kinds of rumour and their impact. A major issue that emerged was the use of digital media: How can you prevent your social media accounts from being used by others to spread rumours? How can the internet be used as a tool for verifying or falsifying information rather than a space where rumours can flourish without being contested? Participants also explored the different components out of which rumours are made, how they go viral, and also discussed the different motivations and interests behind the spreading of rumours.

Several experts relayed information on how investigative journalism deals with the difficulties of fact checking. Activists and researchers from different organizations shared case studies on the detrimental effect of certain rumours on their work and on the perception of what is actually going on, and two former fighters from different factions in the Lebanese civil war explained how they used to spread rumours as a weapon of war.

However difficult the circumstances – even though it might not always be possible to find out the truth behind a rumour –we should not allow ourselves to be complacent. On the contrary, it is our conviction that everybody’s first step on the path to verifying information and countering rumour should be to look critically at the news. When confronted with sensationalist information and images, we need to check the soundness of the sources before blindly ‘sharing’ or ‘liking’.

By Dawlaty: a Syrian organisation committed to democracy, human rights, non-violent activism, and gender equality. The organisation's mission is to enable non-violent activists, groups and civil society organisations to become active participants in achieving democratic transition in Syria, with a particular focus on young people. Since July 2012, the organisation has trained 200 Syrian activists, and has developed and published educational kits and booklets. More information is available on their website (www.dawlaty.org/en).

[i] Haid Haid: Forced Confessions: A Syrian Drama Yet to Reach its Peak. 03.04.2014, http://lb.boell.org/en/2014/04/03/forced-confessions-syrian-drama-yet-r…