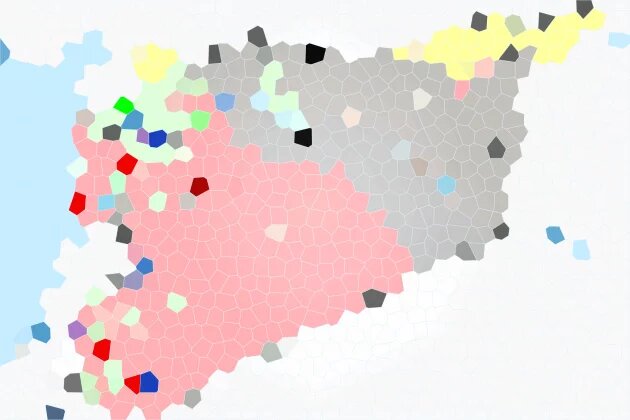

How does the “Islamic State” change the perception of the conflict in Syria? An overview of recent developments and power constellations in the region.

War, it is commonly said, is a last resort. That is a wise notion and one that should be in the best interest of every party. However, it is problematic to use it as legitimation for the choice to perpetually remain in an observant position. ‘Last’ should mean: last possible – when diplomatic efforts are of no avail, and not for when it is already too late.

The Syrian regime has turned the concept of ‘war as a last resort’ inside out. It commenced the war against its own population without seriously considering the reforms initially demanded by protesters. Children were the first victims of the regime, the first victims of torture in the recent conflict, which led to the outbreak of the revolution in March 2011. Rarely did the regime negotiate in the course of this conflict – and when it did, it regularly broke its promises.

Moreover, it is wrong to assume that war only begins at the point when the West intervenes. Syria is a war-ridden country, and anyone standing by and watching, as the West has been doing for three years, bears complicity.

Many times I have heard that there would be no military solution for Syria, only a political one. Naturally, negotiations will be necessary at the onset of a Syria for all Syrians. However, in my opinion it is irritating to distinguish between ”political” and “military” and to treat them as mutually exclusive opposites. The aim of military force would not be to eradicate the opponents, but rather to finally arrive at serious political negotiations. The question therefore is rather whether a political solution can be achieved as long as military options are excluded.

Looking the Other Way, Trivializing

When examining a bloody conflict like the one in Syria it seems cynical to speak of ‘salami-slicing’. Yet that is an accurate description of the tactics the Syrian regime has practiced. At the outset, there were approximately ten people killed in demonstrations on a daily basis, until the West got accustomed to this death toll. Riflemen were succeeded by tanks, tanks were succeeded by air force. The number of missing and abducted persons soared into the tens of thousands. However, the violence only increased gradually and therefore soon failed to cause an outcry.

Part of the subtle trivialising of the revolution was this question, popular in Western circles: how high a price was acceptable for a revolution? As if it was possible, viewing from the outside, to reach a judgement over what degree of oppression grants people the right to resistance.

In Germany, this question gained popularity through constitutionalist Reinhard Merkel who wrote that, given the severe death toll in Syria, the price of the revolution was too high. That is true. 190,000 people or more have lost their lives. Nearly half of the Syrian population have fled their homes. However, formulated in this way, blame is implicitly laid on all those who rose up for their freedom and dignity.

Up until 2011, it was convenient for the West to tolerate Assad’s deathly silence. Yet it was precisely this system of unfairly distributed privileges and arbitrary oppression that ultimately led into chaos. It was not the revolution that entailed suffering in Syria, but rather the regime that practiced brutish suppression.

After 40 years of dictatorial despotism, it should not come as a surprise to us that no oppositional “shadow government” and no easy concept for a replacement of the regime exists. Quite the contrary – we should rather appreciate somewhat with awe how many initiatives in the country, in spite of adverse prerequisites, aspire to a counter-model to authoritarianism and violence. Of course it is problematic that the Syrian opposition, even after three years, is still fragmented. However, part of the reason it is in that condition is that its foreign supporters are at strife as to what they expect from the opposition.

The slogan “Assad forever! Or we will burn the country down,” sprayed onto walls by the regime’s militias in areas they had raged in previously, attests to the fact that the regime is primarily concerned about its own survival. They have remained true to their motto.

Palestinian intellectual Elias Khoury comments that the dichotomy of this infamous sentence does not actually exist. “The nation has been burned to the ground and its population dispersed, so for what do we need Assad now?”, he provocatively asks in his recently published essay.

The War within the War

Whilst the West assumes a largely observant role in relation to the conflict, other parties are intervening massively in Syria. Everyone identifies their very own “war within the war”. Amongst others, Iran and the Lebanese Hezbollah are taking military action on the side of the Syrian regime. They have chosen to support the regime, for better or for worse.

Russia, another great financial and material supporter of the regime, furthermore prevents a mandate for an intervention in Syria in the UN Security Council. In the eyes of Moscow, the conflict is of strategic interest and a trump with which it can demonstrate power at an international level.

Turkey demanded the resignation of Assad early on, but now seems to be more interested in preventing a strengthening of Syrian Kurds.

The fact that Western states have to this day not decided which part of the opposition they trust with the task of steering the country’s fortunes has increased the chances for other states to exert influence. From an early stage on, the discussion in the West centred on reasons why a military intervention in Syria was not possible. In the light of that, political and civil measures were pushed into the background. Every cent of even humanitarian aid was eyed critically as it could potentially fall into the “wrong hands”.

The West largely surrendered the area of military opposition to sponsors from countries such as Saudi-Arabia and Qatar, which was crucial for the appearance and orientation of the armed groups. Military support from the West occurred in an erratic fashion. The weapons the opposition demanded in order to defend itself from the regime’s superiority, anti-aircraft missiles in particular, never arrived. Whenever rebels were supported by the West, it was in such a manner that they would not be able to gain the upper hand.

The possibility of a no-fly zone, as practiced in parts of Iraq in the 1990s without any active military intervention, was ruled out from the outset.

No Intervention is Also an Intervention

Each time the international community announced it would not intervene with military means, the Syrian regime felt approved in its violent strategy and scaled the next stage of escalation.

When US president Barack Obama defined the deployment of chemical weapons as the ‘red line’ in August 2012, the Syrian regime felt it had been signalled green light to use all other types of weapons. The proclamation was immediately followed by an increased deployment of cluster and incendiary bombs as well as air strikes systematically targeting queues in front of Syrian bakeries, as documented by Human Rights Watch.

The international community had barely started patting itself on the back in September 2013 after having successfully negotiated the destruction of the arsenal of chemical weapons with Assad, when the Syrian air force increased their bombardments using barrel bombs. In its only resolution concerning Syria, the UN Security Council called for the abandonment of these improvised weapons in February 2014. The regime has since burnt entire residential quarters to ashes with these bombs. The international community fails to comment on this.

If there is a lesson to be learnt from the history of the Assad regime’s international relations under Hafez al-Assad as well as under his son Bashar, it is: as long as the regime does not feel threatened itself, it will not make any significant changes.

Theory vs. Practice

In the study of political science, one core principle in the comparison of systems is that the ideology of one system cannot be compared with the practice of another. Yet precisely that is the mistake made by many of those who weigh up the terror militia ISIS against Assad.

ISIS is perceived as the personified evil abroad and by most Syrians alike – and ISIS takes pride in it. Its reign is based on unscrupulous brutality. Insofar, the West recognizes ISIS exactly as what it is. However, despite all lived and staged atrocity geared towards the media, ISIS, to date, is responsible for far less deaths than the Assad regime.

The death suffered by thousands of opposition members in Assad’s prisons is no more merciful than the murders committed by ISIS. However, this death is not publicly staged. It takes place away from the public spotlight, in the torture chambers of intelligence services. This renders it possible for many members of the public to ignore these victims.

Whilst ISIS openly prosecutes religious minorities and thereby causes a justified outcry from the West, many lose sight of the fact that most victims of ISIS are Sunnis – Sunnis, which fight against ISIS. Assad’s actions against minorities are more perfidious. Members of minority groups oftentimes support Assad not only because they view him as a protector. Rather, through the regime’s tactics of scaring them into subservience and stoking resentment against them, many of them have entered a devil’s bargain.

Any member of a minority group who actively supports the opposition is being prosecuted just as relentlessly as others are. A sorry example of this is the son of Christian opposition leader Fayez Sara, who was tortured to death by the regime during the Geneva II negotiations. He is only one of many.

Assad as an Ally in the Fight against Terrorism

With the capture of Mosul and the foundation of an ‘Islamic State’, Assad became internationally respectable again. The reign of terror of an Islamic entity seemed so menacing that some considered Assad – in theory at least a secular ruler – as a potential partner to co-operate with.

This was not a new phenomenon: following the attacks on September 11th, 2001, the US and their confederates were in search of allies against al-Qaeda and discovered the Syrian regime. In part, the co-operation worked smoothly – for example when alleged terrorists were flown to Syria where they were to disclose information under torture. Mohammad Haydar Zammar, a businessman from Hamburg, Germany, with Syrian roots, would be able to offer interesting insights into this co-operation. He was abducted and extradited to Syria, where German authorities were present during questionings. However, Zammar, since his release from prison in Aleppo in 2012, has disappeared in Syria and is no longer able to bear testimony as to the adverse conditions in which this co-operation took place.

Whoever advocates Assad as an ally in the fight against extremism must be aware of the fact that that means a clear rejection of human rights, that it means bonding with one of the worst violators of human rights.

This however belongs to the nowadays easily criticized category of ‘ethics’ in international relations. In view of the challenge posed through ISIS, one must think ‘realistically’. The goal should be to fight ISIS with all means, in order to prevent its fight from spreading to Europe or the US.

Yet even from a ‘realistic’ perspective it demands an intellectual contortion act to explain how, of all people, Assad’s regime could play a positive role.

After 2003 – when Assad portrayed himself as a partner in the fight against terrorism – there was, after all, no denying that the majority of jihadists infiltrating Iraq originated from Syria –that oftentimes these people were Islamists that had even been recruited by the Syrian regime itself, in an attempt to build up a force against American troops and to destabilize the country. At the time, Syria was deemed an aspirant for the ‘axis of evil.’ The latter was an unfortunate construct which is luckily no longer referred to. Still, to believe Assad when he offered himself as an ally in the battle against an extremist evil only works in a vacuum devoid of facts and history.

Establishing what role the regime played in the development of ISIS will surely be a fruitful research topic in the future. However, seen pragmatically, this is crucial: Neither is ISIS significantly involved in the battle against Assad nor vice versa. In June of this year ISIS did indeed begin with selective attacks on military bases in eastern Syria. Apart from that, however, the terror militia settled in locations where other rebels had already won the fight against Assad. Assad, for his part, targets not ISIS with his bombardments, but similarly limits them to attacks on other rebels.

Air Strikes against ISIS

In the aforementioned model where every party pursues their own agenda in Syria, where everyone chases after the illusion that they are making improvements by merely getting involved selectively in this complex conflict, that is precisely where recent air strikes against ISIS fit in. ‘Too little, too late, too one-sided,’ that reflects the opinions of many Syrian activists who experience Assad as a threat just as severe as ISIS. The US is involved in training programmes for the Free Syrian Army and other opposition members with the aim for them to fight against ISIS – and explicitly not against the Syrian regime.

This selective approach bears the risk that Americans could be making new enemies. Exactly this had been observed before in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is dangerous once it seems as if the West is not only battling a small group of extremists, but is rather fighting against an entire religious denomination. The fight against ISIS can only be won with a broad support base in the population, and not against it.

In 2011, the West justified its passivity by claiming the consequences were incalculable, that if the Assad regime would fall, a power vacuum could be the result which in turn would elicit anarchy and the collapse of the entire state.

This is already the case or is becoming apparent, even though – or precisely because – Western states did not intervene. Whilst there was no guarantee that an intervention would lead to an improvement, there is no denying: without an intervention, the situation has deteriorated more and more. The only expectation one can have now is that this trend will continue as long as there is no political will to put an end to it.

Some might believe it to be too late to get meaningfully involved in Syria. However, I am convinced that it is now more urgent than ever to work on a solution. We can no longer watch on idly. Or, in the words of Syrian activists: “You send wreaths. But you should never have let the murders happen to begin with!”

How can the West cease the bloodshed in Syria and take the responsibility to protect seriously in view of the paralysis of the UN Security Council? How can the spread of the conflict to other parts of the region be prevented? How can European politics work towards achieving the transition in Syria, as agreed upon with Russian approval in Geneva in 2012?

Most civilians killed in Syria are victims of air strikes. At the moment, the coalition against ISIS and the regime virtually share the sky above Syria. However, is there still the possibility to create protection zones for civilians?

And how can more uniform Euro-American politics be conceived of, which will exclude individual states from picking and choosing their own interest groups and thereby aggravating the conflict?

I am delighted to see many outstanding speakers in our midst today who will tackle some of the questions that are of great importance to German and European politics[i].

[i] This keynote speech was held by Dr. Bente Scheller at the hbs Syria conference “Syrien: Neue Aufmerksamkeit für einen alten Konflikt” in Berlin on November 5th, 2014.