The contribution of the Arab world to global Green House Gas (GHG) emissions is estimated at 4.2%. This includes extreme variations such as the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) producing 85% of the region’s GHG emissions, and Qatar having one of the world’s largest per capita carbon footprints while Yemen has one of the world’s smallest.[1] Overall the region has some of the highest emissions intensity (tonnes CO2 equivalent /GDP) in the world.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), came into force in 1994, and yielded the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The Kyoto Protocol set legally binding GHG emission limits to industrialized countries, and non-binding limits to developing countries. It was the first multilateral agreement that mandated a country-by-country reduction in GHG emissions. However, the implementation of the agreement was poor and not uniform across nations, and it was widely viewed as a top-down approach with countries being ‘forced’ to adhere to limits set by others.

A new UNFCCC climate change agreement has since been adopted in Paris in December 2015. Under this agreement, and in contrast to the Kyoto Protocol, countries around the world have voluntarily indicated the level of commitment they are willing to make to the reduction of their GHG emissions. This approach has created an environment in which the countries of the Arab region are now expected to become part of the global fight against climate change and its impacts, by taking climate change action at a national level. Such actions are reflected in the ‘Intended Nationally Determined Contributions’ (INDCs) that countries, including all the Arab states, submitted to the UNFCCC prior to the 21st Conference of the Parties in Paris in 2015. Given this context, the commitment of Arab countries to action on climate change at the national level is a question being asked, and one that should be answered.

INDCs are to all intents and purposes national action plans, including policies, which countries put forward as part of their contribution toward the global goal of limiting the increase in average global temperature to well below 2oC above pre-industrial levels. As the INDCs of the Arab countries are generally guided by already existing or planned policy, having a closer look at the INDCs of Arab countries provides an indication of their level of commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation on the national level.

The timeline of INDC submissions from the Arab countries, shows that those who were already better established in their climate change policies, and considered more progressive, submitted their INDCs at a significantly earlier stage than the ‘hesitant’ countries, most of whom were from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). In fact, it came as a surprise to many observers that the latter did actually submit their INDCs.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions of Arab Countries as indicators

Morocco was the first Arab country to submit its INDC. This is in keeping with the pressure that comes with Morocco’s status as host of the 22nd Conference of the Parties in 2016. Morocco’s INDC is one of the most ambitious presented by any of the Arab countries and includes both mitigation and adaptation actions. In terms of mitigation, the North African country plans economy wide GHG reductions of 13 percent below ‘business as usual’ levels by 2030, using 2010 as the base year. Not surprisingly, knowing the solar energy potential that the country has, Morocco has an ambitious goal of reaching 50% renewable electricity production by 2025.[2] It also plans to reduce fossil fuel subsidies, which is an important signal about the seriousness of its climate change intentions. On the adaptation front, the Kingdom plans to devote at least 15% of its overall investment expenditure to adaptation actions including the water and agriculture sectors.[3] All of the intended actions to reduce emissions in Morocco are rooted in national priorities and policies, such as the National Strategy for Sustainable Development (NSSD), the National Strategy to Combat Global Warming (NSGW), the Green Morocco Plan (GMP), the Green Investment Plan (GIP) and the Moroccan Solar Plan (MSP).[4] Despite its low contribution to global emissions both historically and currently, Morocco is already one of the more progressive countries in the region when it comes to policy planning for climate change.

Tunisia, which was the fourth country to submit its INDC, has, placed climate change relatively high on its political and economic agenda. It is the first country in the region to recognize climate change in its new national constitution. The new climate clause obliges the state to guarantee, ‘a sound climate and the right to a sound and balanced environment’.[5] In Tunisia’s INDC, submitted prior to COP21, the country plans to reduce its carbon intensity by 13 % by 2030, unconditionally, also using 2010 as the base year.[6] Like Morocco, the energy sector will be the major source of the country’s reductions with the share of renewable energy in electricity production set to increase to 14% by 2020 and 30% by 2030.

As for adaptation action, Tunisia estimated in its INDC a total of 1.9 billion US dollars of funding would be needed during the period 2015-2030. Tunisia’s national climate change strategy (2012) and sustainable development strategy (2014-2020) along with Tunisia’s Solar Energy Plan provide a suitable anchor for the INDC presented by the country. According to Donovan et al (2013), ‘The national climate change strategy defines methods, activities and targets that are, in comparison to other mid-income countries, highly ambitious’.[7] As one of the few Arab countries with little by way of national energy resources, Tunisia is highly dependent on natural gas imports and therefore has a strong interest, as well as an opportunity, for further development of renewable energy. This in turn would also make the country less vulnerable economically.

Among the Arab group are the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council whose economies rely on oil as their main source of export and fiscal revenues; this was clearly reflected by their ‘cautious’ INDCs. Saudi Arabia's INDC indicates that it will pursue economic diversification and adaptation with the aim of generating mitigation co-benefits. The INDC is contingent on: the country's economy continuing to grow; continuing robust oil export revenues, and economic and social consequences of international climate change policies and measures not posing a disproportionate or abnormal burden on the country's economy.[8] Qatar, the country with the highest carbon footprint per capita, presented an INDC similar to that of Saudi Arabia with continued economic diversification and mitigation co-benefits at its core.[9] In recent years the GCC countries have already adopted a number of policies to diversify their economies and reduce their reliance on oil. This is likely to be the result of their realization of the vulnerability of their economies, due to their dependence on international oil markets,[10] and has not necessarily been motivated by climate change mitigation purposes.

In recent years the United Arab Emirates has distinguished itself with regards to national climate change policy, without breaking the united front of GCC on the international arena. The UAE recently restructured its national institutions to create an independent ministry for climate change and has announced the planned phase out of oil exports. The Emirates INDC is supported by current policy such as the UAE Vision 2021, Green Growth Strategy and Innovation Strategy as well as several renewable energy and energy efficiency plans and projects.

Still within the region are Arab countries who are highly dependent on energy imports such as Jordan and Lebanon. Jordan was the first Arab country to develop a national climate change policy in 2013.[11] The high cost of importing energy and the associated risks with a potential increase in prices has lead Jordan to develop its policy on energy efficiency and diversifying energy sources; updating the Energy Sector Master Strategy (2007-2020). Nevertheless, Jordan’s INDC is not considered as ambitious as it could have been, with the kingdom seeking to increase its renewable energy to only 10% by 2020.

Lebanon on the other hand appears to be quite progressive in terms of its submitted climate change actions with an unconditional target of a 15% reduction in national GHG emissions by 2030, mostly from the energy sector. Lebanon’s INDC is rooted in several sectorial policies as the country still lacks a national climate change strategy. Even though Lebanon appears to be taking steps towards moving climate change up its national agenda, any progress to be made in that regard will depend on the success and seriousness of translating the policy into action. To date this remains a weak link. In regard to adaptation, Lebanon has already made some progress in mainstreaming climate change adaptation into the biodiversity (draft National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, NBSAP, 2015), water (National Water Sector Strategy, 2012), and forestry and agriculture sectors (National Forest Plan, NFP, 2015 and Ministry of Agriculture Strategy, 2015).[12] However, the level of integration of climate change adaptation within sectorial policy remains shallow and insufficient considering the vulnerability of the country to the impacts of climate change.

Egypt too proves to be highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Egypt was one of the first Arab countries to realize the threat that climate change poses to its future development and as such has worked towards improving its understanding of this vulnerability.[13] This is strongly reflected in its INDC which is much more focused on adaptation and building resilience than other countries of the region. Its adaptation actions are a reflection of the Egyptian National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction (2011) as well as the Egyptian National Strategy for Sustainable Development.

Climate Change Policy in Arab Countries; varied levels of advancement but far from expectations

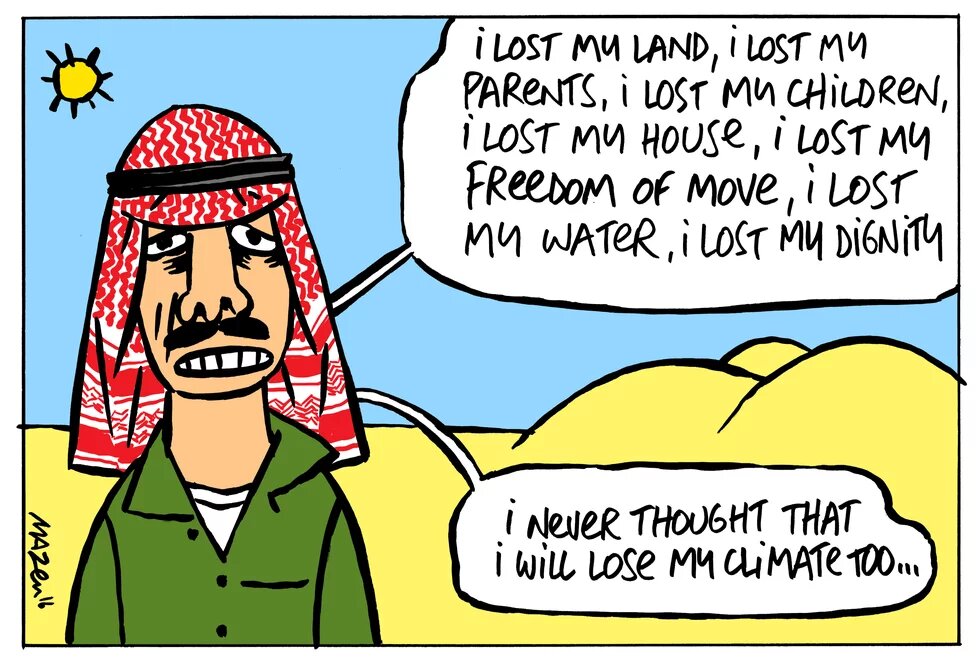

Despite the progress made in Arab countries in recent years, still not enough is being done in a region projected to be highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Mitigation policy remains subject to national interests and especially vested economic interests, while adaptation policy remains by and large fragmented and imbedded within sectorial silos. In a region that is facing security issues, stability issues, mass migration, resource scarcity, and economic dilemmas, climate change is overshadowed by other priorities; despite the fact that many of these problems could be a result of an already changing climate.

The region in general is more concerned with adaptation to than mitigation of climate change, and with the impacts of climate change already starting to be felt, adaptation will certainly be necessary as a survival mechanism. This can be sensed in policies related to water scarcity, which is already high on the agenda of several countries in the region - as a national security priority. Mitigation actions will also witness a boost in Arab countries as the economic benefits become more and more apparent; the region has a high renewable energy potential and a wide margin for energy efficiency improvements. However, policies to facilitate such actions may not be as fast in arriving as could be hoped for.

The new Paris Agreement, with all the financial and technical opportunities it provides, is expected to act as an important incentive for Arab countries to start prioritizing climate change policy. However, this may prove to be a longer transition for some Arab countries, especially the major polluters of the GCC states.

[1]Waterbury, J. (2013). The Political Economy of Climate Change in the Arab Region, in United Nations Development Programme Regional Bureau for Arab States. Arab Human Development Report; Research Paper Series.

[2] Morocco: Intended Nationally Determined Contribution under the UNFCCC http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Morocco/1/Morocco%20INDC%20submitted%20to%20UNFCCC%20-%205%20june%202015.pdf (accessed May 4, 2016)

[3]Chan, H. Morocco First Arab Country to Submit Climate Pledge Ahead of Paris Negotiations. June 11 2015. https://www.nrdc.org/experts/han-chen/morocco-first-arab-country-submit-climate-pledge-ahead-paris-negotiations (accessed May 5, 2016).

[4] Raven, M. Morocco's INDC - A strong signal coming from the first Arab country, June 10 , 2015, http://www.climatenetwork.org/node/5211#sthash.zacLo4Ej.dpufhttp://www.climatenetwork.org/node/5211 (accessed May 8, 2016).

[5] Paramaguru, Kh. (2014). Tunisia Recognizes Climate Change In Its Constitution. Time.

29 January. http://science.time.com/2014/01/29/tunisia-recognizes-climate-change-in-its-constitution (accessed May 5, 2016).

[6] The road towards COP21: an overview of INDCs from the MENA region. Climate Policy Observer, 18 September 2015. http://climateobserver.org/the-road-towards-cop21-an-overview-of-indcs-… (accessed May 7 , 2016)

[7] Duchrow, A et al. (2013) Adapting to Climate Change. Focus Tunisia. http://revolve.media/adapting-to-climate-change (accessed May 24,2016)

[8] The Intended Nationally Determined Contribution of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia under the UNFCCC http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Saudi%20Arabia/1/KSA-INDCs%20English.pdf (accessed May 5, 2016).

[9] State of Qatar Ministry of Environment Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) Report http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Qatar/1/Qatar%20INDCs%20Report%20-English.pdf (accessed May 5, 2016).

[10] Callen, T. et al. (2014) Economic Diversification in the GCC: Past, Present, and Future. IMF Staff Discussion Note,

December 2014.

[11] Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Jordan/1/Jordan%20INDCs%20Final.pdf (accessed on May 4, 2016).

[12] Republic of Lebanon Lebanon’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Lebanon/1/Republic%20of%20Lebanon%20-%20INDC%20-%20September%202015.pdf (accessed on May 6, 2016).

[13] Gelil, A. (2014). History of Climate Change Negotiations and the Arab Countries: The Case of Egypt, Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut, 2014 https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/public_policy/climate_change/ifi_cc_texts/Documents/20140723_Abdel_Gelil.pdf (accessed May 5, 2016).