Preamble

Various studies have shown that the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region faces a multitude of threats to its biodiversity and natural ecosystems, as a result of habitat loss and the general land degradation processes associated with human expansion and economic growth.[1] The region is at a crossroads and must address an increasing number of pressing developmental and environmental challenges, all of which are taking their toll on the region’s fragile ecosystems. To ensure sustainable development, collective efforts are needed to address human development, and ecosystem conservation, along with enhanced governance of the region’s primary resources.

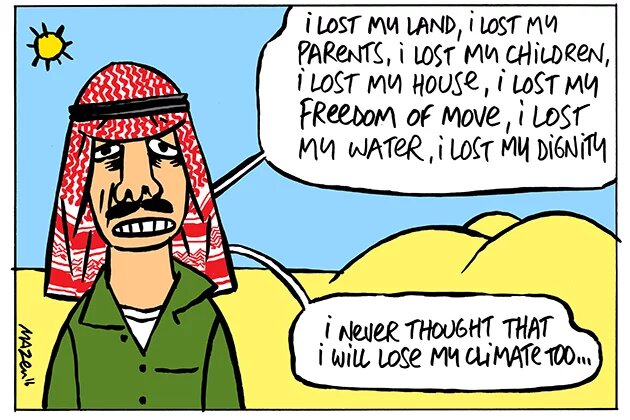

The Arab region’s climate has already begun to change, often to the detriment of Arab society.[2] In the 2012 report from the World Bank ‘Turn Down the Heat - Confronting the New Climate Normal’,[3] the ‘MENA’ region is identified as a climate change ‘hot spot’. This is because of its high vulnerability to the consequences of an average temperature increase of + 2°C by 2100, (on current projections the most optimistic scenario). Risks related to climate change such as decreased rainfall, increased drought, and rising sea levels will exacerbate the increasing human pressures the region is already facing.

The flagship report on adaptation to climate change in Arab countries launched in 2012 by the World Bank and League of Arab States indicated that in rural areas climate change is forcing communities to rethink long-standing gender roles that have perpetuated gender inequality.[4] Climate change will threaten the basic pillars of development. Men and women possess unique vulnerabilities to the impact of climate change, based on their respective roles in society. In most countries in the region women will face the brunt of the impact of climate change. This is because they are often poorer than men; responsible for natural resources and household management; lack access to opportunities for improving and diversifying their livelihoods, and have low participation in decision-making.

Many climate change adaptation interventions and policies in the region have taken place without a proper understanding of how and why they were planned and how they needed to be implemented. Although most of the state interventions regarding adaptation and mitigation are legislated by the government in question, such interventions have often harmed rather than benefited human well-being, and had a negative effect on ecosystem resilience. In this context gender inequalities and perceptions of traditional roles affect not only women, but can also result in men facing specific vulnerabilities.[5]

This paper argues that climate forces are likely to raise gender specific issues in the region and explores how we can leverage the required political commitment to facilitate a holistic approach toward mainstreaming gender responsiveness to climate change actions in Arab countries.

Gender Indicators and Climate Change in the Arab Region

Research has shown that gender analysis is a tool that can aid our understanding of not only the specifically gendered elements of climate change, but a range of broader socioeconomic, cultural, and structural equality issues embedded in climate change strategies. To ensure an effective, gender responsive, strategy to climate change we need to determine the types of representation, the roles and responsibilities, rights, adaptive capacities, forms of resilience as well as the risks, and vulnerabilities, that pertain to women, to men, to girls, and boys at all levels.

In the MENA region there are gender specific indicators and general social indicators that acknowledge the disadvantages of women in this region compared to other parts of the world. In social, political, and economic terms, women lack access to resources that are more widely available for men. Figure 1 represents the gender gap index of the nations in the MENA region. The higher the score in the ‘Gender Gap Index’, the closer the country has come to closing the ‘Gender Gap’ – ‘1’ would represent total equality and ‘0’ absolute inequality.

As can be seen from the above figure, most of the countries in the region scored higher in the gender gap index in 2014 compared to 2010, indicating a slight improvement in gender equality between these years. However, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Iran, achieved lower scores in 2014 than in 2010 indicating worsening gender equality in these states. Therefore, while the general picture is one of a slight improvement in gender equality across the region, the picture is not uniform, and some states appear to be moving backwards. However, what can be clearly attested is that all across the region women still face significant discrimination. Even as the highest-ranking economies in the region have made vast investments in increasing women’s education over the last decade, most countries have had limited success in integrating women into the economy and decision-making processes, and as such are failing to reap the benefits of this investment.[6]

For example, many women in agriculture are still forced to do unpaid work, and the female labour force outside of the agricultural sector is very small, and often poorly paid. Very few women are able to attain the resources to become entrepreneurs. Moreover, in most countries female ownership of agricultural land is less than 10% with Qatar and Saudi Arabia having 0% of women owning agricultural land.[7]

Across the region women still have a literacy rate 15% lower than men. They have little voice in decision making; women’s representation in Arab governments is only 9%, or half the global average. This is even the case in some Gulf countries where more women than men graduate from university. Women in the Arab world have low rates of political participation - in all countries, except Tunisia, less than 20% of seats in parliament are held by females. The lack of women in parliament and ministerial positions constitutes a barrier to involving more women in environmental issues because they are not able to sit at the decision making tables. Among the 18 countries studied in the IUCN Environmental Gender Index 2013 pilot, it was found that the MENA region had the lowest rate of female participation in international environmental conventions. Lebanon was the highest performer in the region, introducing into national policy the gender and environment mandates in the three Rio Conventions, and for the implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), whereas Yemen was presented as an example of one of the lowest performers.

Yemen represents an unfortunate reversal of a promising development in the region. Although considered one of the most gender-unequal countries in the world, Yemen had identified the importance of rising civic participation and inclusion with a special focus on women and youth in its country assistance strategy with the World Bank. With this as the guiding principle the mainstreaming of gender considerations throughout the country portfolio resulted. Unfortunately new developments in Yemen have reversed these efforts to advance women’s rights and halted opportunities to increase the inclusion and participation of women in civic and economic life. Ultimately, effective adaptation to climate change can only be ensured if barriers to gender equity are removed and women are empowered to contribute to climate change actions. There is a real risk that such recent policy transformations, along with the numerous conflicts in the region will exacerbate the existing social, economic and environmental stresses, increasing the damaging effects of climate change, and reversing previous developmental and conservation achievements.

Political Will Does Add Value for Gender Equality in Climate Change Actions for Arab Countries:

In Arab countries a significant number of steps have been taken to address formal policies and informal practices which cause and perpetuate gender inequalities and increase vulnerability to climate change. Table 1 below shows some different Arab countries progress toward environmental mandates and the gender dimensions which, as well as promoting gender equality, are a substantial element in the ‘Intended Nationally Determined Contributions’ (INDCs) under the new international climate change agreement.

With the increasing attention to the implementation of the international conventions on climate change and desertification, along with achieving the Aichi biodiversity targets in Arab countries, the region needs to ensure it has the needed capacity and guides to integrate a range of different indicators in a transparent and effective manner. This will play an important role in helping their communities to achieve sustainable livelihoods, poverty alleviation, environment protection, and conservation of the natural world. Lessons can be learned from Jordan, Egypt and Morocco on how to ensure country resilience and adaptive capacity for climate change, and in achieving the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with more equality and a holistic perspective.

Jordan: Leading in Developing Gender and Climate Change Action Plans

It is clear that Jordon has taken significant steps in recent years: a number of economic and social policies along with new legislation have contributed to the improvement of the position of women in Jordan in all fields.

In 2010, Jordan became the first country in the Arab region to address the linkages between gender and climate change by creating the ‘Program for Mainstreaming Gender in Climate Change Efforts in Jordan’.[8] Jordan’s plan of action was approved by the Government and endorsed by the National Women’s Committee. It will guide the future policies and positions of all agencies addressing climate change. The program’s objective is, ‘to ensure that national climate change efforts in Jordan mainstream gender considerations so that women and men can have access to participate in, contribute to, and hence optimally benefit from climate change initiatives, programs, policies and funds.’ [9] The programme has had an impact on the National Women’s Committee, enabling them to address climate change issues. The National Women’s Strategy, launched in 2012, includes a section on ‘women, environment, and climate change,’ with the goal of Jordanian women being active and empowered to maintain and develop natural resources. Building on the 2010 programme, as part of the enabling activities for the preparation of Jordan’s third ‘National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’ (UNFCCC) in 2013, gender was expressed as a national priority in the context of climate change. Most recently, Jordan integrated gender as a major factor in its ‘National Climate Change Policy of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 2013-2020’. In 2015 Jordan integrated gender responsive actions into its INDCs.

However, although these achievements were significant, ensuring ongoing responsive action is a more complex task, with many overlapping and emerging factors such as the influx of Syrian refugees and scarcity of natural resources. Furthermore, the National Inter-ministerial Committee on Climate Change, the main body responsible for providing guidance on initiatives relating to climate change, has not been active in ensuring that projects and initiatives under its consideration are in line with the principles of ensuring gender inclusion. There is a need to enhance the partnership between the Jordanian National Commission for Women’s Affairs and the National Inter-ministerial Committees on Climate Change to merge gender and climate change actions, through follow up, control, evaluation and development.

Egypt: Political Fluctuations Threaten Gender Equality

The Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency has established a women's unit in the ministry to improve the role of women, this is a key component of its environmental policy. In May 2011 the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency in cooperation with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) produced a ‘National Strategy for Mainstreaming Gender in Climate Change’. The aim of the strategy was to contribute to a deepening understanding of the value of incorporating gender in both the development and implementation of policies and measures relating to adaptation and mitigation. Along with this they also sought to demonstrate the potential contribution of a gender perspective to the sustainable development of the principal economic sectors in Egypt. As a result in December 2011 a national strategy for adaptation to climate change and disaster risk reduction emphasized the role of women in adaptation actions.

Despite having such a strategy, recent political transformations have failed to safeguard the rights of women. This was especially evident when the National Council for Women refused the claim by Egypt’s Muslim brotherhood that the UN declaration calling for an end to all violence would lead to the complete disintegration of society.[10]

Based on this transformation and despite the fact that the new reform is re emphasizing the role of women and their rights, Egypt’s Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) do not include a single reference to gender or women. Therefore, to avoid the impact of recent political reforms, the adoption and strengthening of sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels should be ensured. This could be implemented through critical mechanisms for monitoring, funding and the enforcement of new policies. Moreover, national institutions working on developmental issues, peace and security should be trained to re-highlight the role of women and ensure gender equality.

Morocco: Real Steps Toward Gender Equality in Climate Actions

Morocco has had several achievements in accordance with its international obligations in the field of human rights in general, and of women in particular. In 2006 a national strategy was developed for gender equality and equity. The strategy focuses on: civil rights, representation and participation in decision-making, social and economic rights, social activities and individuals, institutions and policies. One of the main priorities for the Ministry of Solidarity, Women, Family and Social Development is to ensure a collaborative approach to gender equality between ministerial departments, NGOs and other organizations. A ‘Committee for Gender Cooperation’ has also been established to ensure the monitoring of the gender responsive budgeting that publishes gender budget statements on a yearly basis.

The government of Morocco is making extensive political and strategic efforts to conserve their ‘ecosystem services’ taking into account climate change risks. Respect for human rights and gender balance are two pillars of Morocco’s vision for its work on climate change. In 2015 Morocco launched its INDCs and has put in place a system to monitor and assess vulnerability and adaptation to climate change taking into account gender issues.

The Moroccan Ministry of Solidarity, Women, Family and Social Development incorporated with UN WOMEN to draft a new gender equality plan which will be used in the environmental and sustainable development sectors in the Kingdom. It is hoped that this step will further enhance the achievement of the country’s vision in climate change actions.

Ahead of hosting the 22nd Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP22) the Moroccan government sent a message to COP 21’s Gender Day emphasizing the positive contributions of women in the fight against climate change, as well as the key challenges and opportunities for their contributions in this area. Hosting COP 22 will ensure that Morocco continues to address gender equality and shows a positive case from Arab countries working toward gender responsive lessons in climate change actions.

Recommendations

Based on the previous cases, it is important to understand what adaptation to climate change is and how it relates to people, communities, countries, and regions. It requires integrated, multidisciplinary, multi-sectorial planning, for developing, implementing, and evaluating strategies to understand the consequences of interventions. Only as such can it ensure that positive benefits are achieved and equally distributed. Beyond the old adage of adapting in ways that have ‘no regrets’ and that ‘do no harm’, while increasing capacity and building resilience, it is important to recognize the ways that these adaptation strategies can contribute to achieving greater goods, such as poverty reduction, equality, and sustainable development.[11]

For gender responsive actions to climate change, national capacities should be strengthened to improve public participation in the development and implementation of policies. Governments should integrate gender perspectives into policies and programs, including:

- Developing action plans with clear guidelines on the practical implantation of gender.

- Incorporating a gender perspective into program budgets.

- Incorporating a gender perspective in operational mechanisms for the new SDGs.

- Ensuring continuous awareness raising and training on gender issues for related staff.

- Involving women in environmental decision making at all levels.

- Promoting and investing in innovative areas of business in rural economies, particularly those that emphasize/improve opportunities for women.

- Recognizing that women as important agents of change; their unique knowledge is essential for adaption measures and policies.

[1] State of Biodiversity in West Asia and North Africa. UNEP, 2010.

[2] Overview and Technical Summary, Adaptation to a Changing Climate in the Arab Countries: A Case for Adaptation Governance and Leadership in Building Climate Resilience. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] IUCN 2013

[6]The Global Gender Gap Report 2014- World Economic Forum

[7] FAO report on Gender and Land- related statistics http://www.fao.org/gender-landrights-database/data-map/statistics/en/

[8] The program was prepared with International Union for Conservation of Nature

[10] The Muslim Brotherhood special Report prepared by Clarion Project Research Fellow Elliot Friedland June 2015.

[11] Lorena Aguilar, IUCN Global Gender Advisor.