Considered among the regional leaders in renewable energy, Morocco has taken on excessive debt while privatizing its nature. The question is whether these new renewable energy sources will lead to real sustainability or become a white elephant?

Morocco's climate objective is to achieve a 32% drop in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030.[1] In 2010, Morocco was ranked 118th out of 176 countries in terms of GHG emissions with 69 million tonnes of CO², equivalent to 1.77 metric tonnes of CO² per capita.[2] With a small economy of 110 billion USD GDP, and very low investment in the industrial sector, the country has chosen to focus primarily on renewable energy to lower its emissions.

Energy dependence

Morocco is a country dependent on imported energy. According to the Department of Energy 95.5% of the energy consumed in Morocco is imported, whether in the form of coal, oil or electricity. To address this reality, since 2009, Morocco has embarked on a new national energy strategy with clear guidelines.[3] By participating in this process, Morocco aims to optimize the energy mix in the electricity sector, accelerate the development of energy from renewable sources; mainly, wind, solar and hydroelectric; make energy efficiency a national priority, and promote foreign capital investment in oil and gas- ultimately leading to a further regional integration. To support this strategy in 2009 the country announced an ambitious program to diversify its energy mix, and aimed to use 42% renewable energy by 2020.[4]After King Mohammed VI’s speech on 30 November 2015, during COP 21 in Paris, these ambitions were revised upwards. The country now aims to achieve 52% of its energy from renewable resources by 2030.

Dr. Abdelkader Amara, Minister of Energy, Mines, Water and Environment set out the vision as follows:

Between 2016 and 2030 Morocco will develop additional electricity generation capacities of more than 10 GW from renewable sources including 4,560 MW from solar, 4,200 MW from wind turbines and 1,330 MW from hydroelectric. The total investment expected for the power projects from renewable sources will be US $ 32 billion, representing real investment opportunities for the private sector.[5]

This ambition should, by 2030, have led to 19 times what was has been achieved in the last 5 years through solar energy, and the equivalent of 6 times what was achieved in the same time through wind power.[6] It should be noted that all programs are currently running behind schedule.[7]

By setting such an ambitious goal, the country is fully engaging with the international agenda in the fight against global warming. Indeed, by ratifying the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1995 and the Kyoto Protocol in 2002, and in making such important announcements, Morocco wants to position itself as a regional leader in the fight against climate change and the development of a green economy. It is certainly an ambitious project, but also a risky bet on the future, one that generates huge investment needs, needs that the country cannot afford to cover in view of the size of its economy and its overall level of debt: 81.4% of GDP in 2015.[8]

Debts versus climate

A lack of national financial resources is the major issue that Morocco faces in developing its green economy. Indeed, as Said Guemra an expert adviser in energy management with Gemtech Monitoring who has been following the field for almost 30 years-warns: ‘In the absence of our own financial resources, it is the donors who dictate what to do’.[9] On the contrary, Mustapha Bakkoury, the CEO of the Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy (MASEN),[10] argues for the project despite its cost, claiming that Morocco is investing in its future: ‘...to reckon that thinking about sustainable development is a luxury reserved to developed countries is tantamount to lacking in ambition, and it is in contradiction to the things we have already started to implement.[11] But at what price is Morocco implementing its green choice?

In order to understand how Morocco is developing its green economy, an analysis of how MASEN works could be of great help. Karim Chraibi, an expert in energy investment and renewable energy argues that, ‘With MASEN, Morocco has set up a financial tool to pick international subsidies, grants, and concessional loans. Thus, the entire renewable energy program is run by a debt structuring tool.’[12]

Instead of creating a diversified public structure that would meet the need for security of energy supply, Morocco via MASEN has created a tool primarily orientated to financial issues. In the end, Morocco will incur debt by subscribing to international subsidies, grants, and concessional loans, in order to finance private developers who will produce and sell energy to the State. An energy that the State will then resell to consumers at subsidized prices (see Box 1). The green ambition in Morocco will be achievable thanks to a double subsidy (soft loans to the private sector plus subsidized electricity to consumers) and a privatization of profits.

This choice is very much the result of the royal will and it is possible through legal and financial packages (suggested mainly by the World Bank and the African Development Bank, and largely financed by the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau -KfW), that help to compensate for the lack of state funding, and counteract the weak attractiveness of the renewable energy sector for private investors.[13]

However, Morocco’s inability to finance its green economy prevents the country from deciding which kinds of green energy will be developed. As Said Guemra explains:

Whether in terms of technologies or financial arrangements, Morocco is being pushed into a testing phase, experienced but not chosen. The ‘Noor complex’ in Ouarzazate, for example, is unique. Under the leadership of the World Bank, to the benefit of multinationals, and at our expense, we are going to see the implementation on the same site of the three different technologies: Concentrated Solar Power (CSP), photovoltaic, and solar towers. It could be interesting for engineers working on the project, but what accrues to the country if we do not have the economic and industrial structures able to capitalize on this expertise?

This position is reiterated by Karim Chraibi, for whom,

...it is the donors who have imposed the technological choices - because we had no choice! Today CSP technology and storage techniques are far exceeded by the opportunities of photovoltaics.

He warns that

... by locking small private initiatives out through a form of liberalization of the energy sector tailored to large power plants, it is essentially the big international operators who benefit from the development of renewable energy in Morocco.[14] Renewable energy must be a real economic sector creating jobs and value locally, if it is to develop. This is not the case today despite all the investment that has been made.[15]

It is strong lobbying from the financial and industrial sectors that determine both the technological choices made and how the projects are financed. In turn this particular model of implementation of a ‘green economy’ seems to do more to confirm the dependency theory than guarantee that Morocco will be able create a sustainable renewable energy sector.

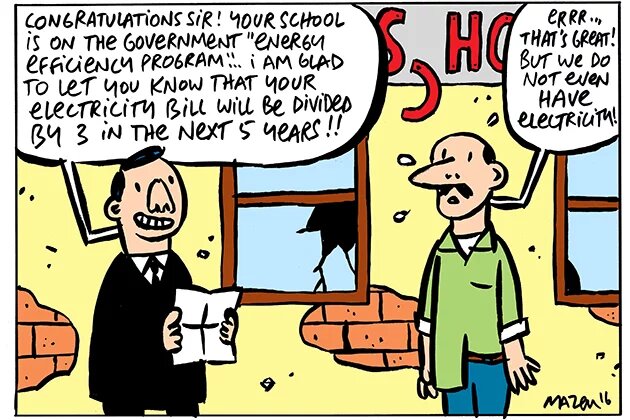

The great absence of energy efficiency

Alongside increased energy from renewables, Morocco’s strategy objectives include increased energy efficiency, and Morocco wants to achieve 15% energy efficiency by 2030.[16] But as Said Guemra wryly observes,

Energy efficiency is not sufficiently valued in the national strategy, even if every kilowatt hour saved is 5 to 20 times cheaper than comparable reductions through renewable energy. But they are not very interested because there is nothing to inaugurate.

He goes on to explain:

We continue to launch studies to explore the potential of reducing the energy bill, so far there have been over 25, and this is updated every year... but then, where are the programs on the ground? Even the regulations put in place are inadequate. For example they insist on lowering the bill for heating and cooling in schools while many schools do not even have an electric connection or lack electrical equipment. These studies are entrusted to foreigners who make a ‘copy and paste’ of what is happening elsewhere. There is a real problem of technical support for the organizations that create the regulations.

For this expert it is a matter of political will and power between donors and the state. In this context he cites the project dealing with the energy efficiency of Moroccan mosques. This project was initiated in partnership with the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), and two public agencies, the Moroccan Agency for the Development of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (ADEREE) and the Energy Investment Company (SIE). However, Said Guemra explains that,

According to the study to develop the project, the 15,000 mosques of Morocco consume 10 million Dirhams (1 million Euros) per year of electricity. I think the cost of generalization of the program is expected to cost 600 million euros. An amount to be borrowed from donors.

An economic aberration for a country that does not even recycles its waste! It therefore seems that many public policies fit more with the agendas of donors than urgent public needs.

The diktat of the market

Whether the program is in renewable energy or energy efficiency, the common point of these initiatives is the liberalization and the increased financialization of these sectors. Financing mechanisms (bilateral, multilateral funding and Climate Investment Funds) or the inclusion of renewable energy programs under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) or the formulas of Independent Power Production (IPP) used since 1997,[17]and their unsustainable environmental impacts (see box 2) all suggest that what drives energy policy is a privatization strategy of our natural heritage, and this is a real concern for the environment. The official communications about the solar program have put forward the possibility of exporting energy to Europe. Through these exports it would be possible to set up an equalization system that would decrease the cost (purchase energy in Europe in the summer, which is the peak period of Moroccan consumption, and sell in winter which is the peak period of European consumption).[18] Imitating European policy, the Moroccan Solar Plan aims to provide green energy for the countries of the European Union as part of their energy mix. But to do this, Morocco needs to strengthen its connections to the European grid in the hope that one day it will be able to export its surpluses including solar and wind power. An investment of 2 billion Euros would be needed to strengthen the connections with Europe and to strengthen existing lines.[19] Such an investment would open up new markets but also incur further debt for the State. Indeed, ‘Nobody wants to pay the initial investment because it does not directly produce cash, and the long term horizon of 50 to 100 years is simply too risky, because it is very difficult to calculate the potential return over such a long period’ claims Gauthier Dupont, Director of Clean Energy & Sustainability Services for Ernest & Young in the UAE.[20] He adds, ‘there are not many private lines in the world because it is difficult to set a ‘pass rate’ since the network grid and the electricity itself selects the lines’.

For its ambition to be viable, the state will have to put its hand in its pocket in order to avoid increased debts. A situation that pushes Mr. Dupont to wonder: ‘should the priority be to export green energy to Europe through all these interconnections or to convey quality electricity to every home [in Morocco]? For him there is still much to do to generalize the quality of electrification ‘prior to pleasing the Europeans with green energy’.

To conclude …

According to the statements by the Minister of Energy, despite tripling the installed electricity production capacity, the planned 52% of the energy mix to be produced from renewables by 2030 will reduce energy dependence on imports by only 15%. Even with a 32% reduction in GHGs by 2030, Morocco will have little impact on global warming. Already a low polluter, contributing only 0.16% of global emissions, [21] the country does not represent a major stake in the global climate. Nonetheless, the proactive policy, pursued by the country who will host the COP22 climate negotiations in Marrakech in November 2016, is often described as a model for the region. But is this what Morocco really needs? The ultra (neo)liberal policy in the energy sector, described above, will condemn the country to paying off debts for the next 30 to 40 years, and has seen the privatization of key sectors such as energy and water. While its objective is to reduce energy dependence on foreign imports, the country is creating another dependence - on multinational energy companies and international financial institutions. With cascading financial and legal arrangements, heavy involvement from the monarchy, a high dependence on foreign donors, the threat of water shortages affecting the functionality of the solar plants, and in the absence of a public debate that would seek accountability around these policies, there is a real risk of creating ‘energy white elephants’.

………………………………………………….

Box 1

Risky assemblages

As an example of complex assemblages in the energy sector, the Ouarzazate thermo solar plant is a case in point. This multi-technology solar plant, capable of producing 580 MW by 2018, will need an investment between 2.5 to 3 billion Euros. To fund this project the Moroccan State is counting on the development of public / private partnerships (PPP) via a BOOT (Build, Own, Operate, Transfer) contract with a Saudi Arabian investor ACWA Power. The deal is simple: the state via MASEN borrows from international donors (the World Bank, the African Development Bank, KfW, the European Investment Bank, the French Development Agency, and others ...) 2.1 billion Euros, it pays this amount to ACWA Power, which sub-contracts construction to Spanish operators with turnkey contracts. Subsequently, ACWA Power operates the plant and sells the electricity generated to MASEN at 1.5 Dirham per KWh - for 25 years. MASEN then resells to the National Office for Water and electricity (ONEE)–for an average of around 1.2 Dirhams per KWh. The difference is supported by a grant funded through another loan from the World Bank. This kind of arrangement will most probably be generalized to other solar and wind projects.

………………………………………………….

Box 2

Water stress

According to official statements, the central Ouarzazate will consume 2 million cubic meters per year. Equivalent to 50% of the water consumption of all inhabitants of Ouarzazate, the city it will illuminate. By opting for the technology of concentrated solar (CSP) the MASEN Project promotes the megaproject while at the same time neglecting the environmental realities of the region. The control unit is directly connected to a pipe from an adjacent dam for its cooling system. Now it happens that this region is arid with only 100 millimeters of precipitation per year and less than 30 mm in dry years.[22] Given the high probability of increased drought, related to global warming processes, this brings into question the sustainability or future viability of the plant. After Ouarzazate, there are 5 further solar stations planned in Morocco by 2030, all are planned in arid or semi-arid areas. A study by the World Resources Institute estimates that Morocco will suffer water shortages by 2040.[23] A frightening possibility which brings into question the viability of such policies.

[1]http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Morocco/1/Maroc%20CPDN%20soumise%20a%CC%80%20la%20CCNUCC%20-%205%20juin%202015.pdf

[4] Ibid.

[5] Intervention of Dr. Abdelkader Amara, Minister of Energy, Mines, Water and Environment of Morocco at the Ministerial Meeting "Energy Partnership Moroccan-German" on 04.19.2016.

[6]Author's calculations from the speech by the Minister of Energy, Abdelkader Amara, available on the official website of the Ministry: http://www.mem.gov.ma/SitePages/Default.aspx. It is important to note the lack of documents related to the progress of various projects.

[7]As an example the Ouarzazate complex was to be completed in 2015. Only the first phase (160 MW to 560 MW) was delivered in early 2016. As for the tender of 850MW wind, to be awarded in 2014, it was finally awarded in early 2016.

[8]http://www.hcp.ma/Synthese-Budget-Economique-Exploratoire-2015-presente-par-M-Ahmed-Lahlimi_a1419.html

[9] Interview with the author on 25/11/2015

[10]On May 6th, Bakkoury announced in the press that from June 2016 MASEN will become the ‘Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy’.

[11] Interview published in the magazine Economie et Enterprises in January 2014. http://www.economie-entreprises.com/mustapha-bakkourypresident-du-directoire-de-masen/

[12]Interview with the author on 12/04/2016

[13] KfW to date has supported renewable energy projects in Morocco with almost EUR 1 billion. Thanks to the Morocco-German energy partnership, this trend will increase until 2050.

[14] The law 13-09 that liberalized the energy sector in Morocco blocks the connection to the medium voltage grid thereby preventing small producers participating.

[15] Interview with the author on 12/04/2016

[16] "Renewable energies in Morocco" presentation document of the Ministry of Energy, Mines, Water and Environment at the "Workshop Mission Morocco" on German Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Morocco (AHK Casa), Casablanca, 20/11/2012.

[17] This is the date of the first privatization of a coal power plant in the small town of Jorf Lasfar to UAE TAQA group. They now control nearly 40% of electricity generation in Morocco.

[19] El Karmouni G. W. (2015). Electricity, Export to Europe will wait. Economie et Enterprises, April 2015.

[20] Ibid.

[22] Kouz K. and al. (2011), "Study of Environmental and Social Impact within the Framework of the Solar Project of Ouarzazate." MASEN, Rabat.