“But my soul will live on in you,” reads the last graffiti on the walls of suburbs in southern Damascus, a message left behind by the former residents before they mounted the infamous green buses to enforced displacement.

On May 21st, regime troops once again captured the – unofficial – Palestinian Yarmouk camp. It had been besieged for years and was reduced to ash and rubble during constant air raids. Yarmouk essentially came to be known in the West by way of two things: firstly, through Aeham Ahmad who now lives in Germany and rose to fame by playing his piano in the midst of the rubble and, secondly, through a photo taken in January 2014 which became symbolic for the extent of the horror caused by the siege: A street, lined with the ruins of bombed and burnt out multi-storey buildings, filled to the horizon with a line of people scrambling for their share of one of the rare UN food deliveries.

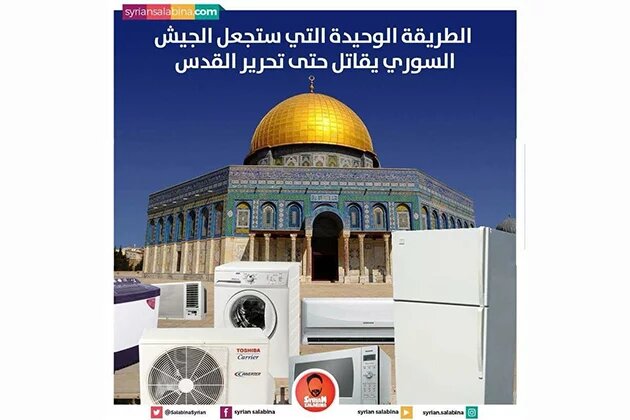

Political researcher Ziad Majed compared the latter to a current image of the very same street. It depicts soldiers dragging off refrigerators, washing machines and any other useful goods from the houses of those displaced – as much as they can carry or load up on carts. “Assadism in two images,” Majed describes the pictures: “After they deported those who survived their siege, barrel bombs and torture, Assad mercenaries & their allies are stealing what remains in sacked and destroyed habitations in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp.” – “This shows how the Syrian regime frees Palestine – one washing machine at the time,” one activist has commented dryly.

When the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London stated in 2013 that the Syrian army’s strength had been severely compromised and had fallen to about half its original size, the institute may have simply applied an incorrect scale. Perhaps the strength of the Syrian army is not measured in its numbers but rather in the amount of household appliances a soldier can carry. Similarly, the regime’s narrative that the localities it has defeated and depopulated have been “liberated” should be taken with a pinch of salt – given that Assad tends to regard civil liberties as negligible, this should be understood in a post-materialist sense: citizens are freed from their belongings. They are permitted to take all they can fit into the buses – that is, with the exception of jewellery and money, as prescribed by all the latest “reconciliation agreements”.

It would be wrong to assume that other groups do not pillage or steal. When the Turkish-allied Syrian-Arab troops drove out Kurds from Afrin, images of lootings soon made the rounds. However, graffiti from the perpetrators started to surface quickly after, expressing remorse over their actions and at least a half-hearted attempt at recovering the possessions ensued. As with torture and the killing of civilians: the regime is also outstanding when it comes to plundering. It does not even purport to take any action against it. “That was already the case when troops were withdrawn from the Lebanon,” a colleague explains. “They took truckloads of household appliances – without the slightest misgivings. The soldiers were badly paid and to compensate for that, the regime allowed them free rein to loot.”

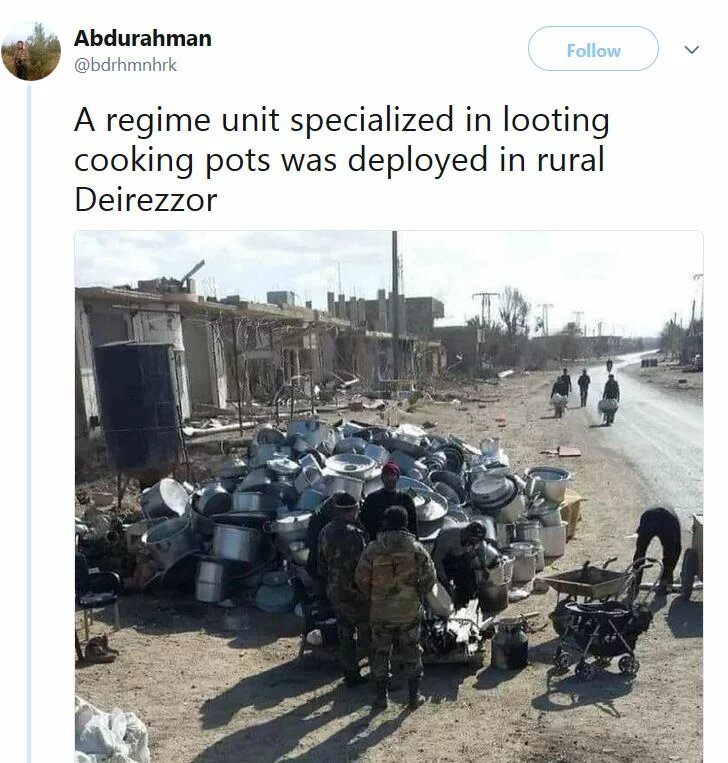

In February, Twitter user “Abdulrahman” added a photo which depicts soldiers guarding an enormous heap of voluminous cooking pots. “A regime unit specialised in looting cooking pots was deployed in rural Deir Ezzor,” he announced while adding a leaflet with suggestions for “new regime army ranks”: The stars on the sketches of epaulettes have been substituted with washing machines, gas containers and fans. When pictures of the raid of Yarmouk were circulated, one Syrian website went even further. Taking inspiration from the regime’s grandiose statements that it promotes the “Liberation of Palestine”, the website announced that the only way to motivate the Syrian army to take action for the cause had been found – a message accompanied by a photomontage of freezers and microwave ovens enticingly arranged in front of the Dome of the Rock.

---

Translated from the German by Christine F. Kollmar