‘The slogan “A land without a people for a people without a land” is at the heart of the hummos polemic’, is how my friend, Rabbi Douglas Krantz, explained the appropriation of hummos as indigenous Israeli sabra food. ‘When I first came here, over 30 years ago, hummos and falafel were ubiquitous and I assumed it was Israeli food. In the States it was advertised as Israeli sabra food’, in reference to the sweet and prickly cactus fruit, sabra, which has come to mean any Jew born on Israeli territory, ironically it is also a commonplace Palestinian backyard fruit used for fencing.

‘The slogan “A land without a people for a people without a land” is at the heart of the hummos polemic’, is how my friend, Rabbi Douglas Krantz, explained the appropriation of hummos as indigenous Israeli sabra food. ‘When I first came here, over 30 years ago, hummos and falafel were ubiquitous and I assumed it was Israeli food. In the States it was advertised as Israeli sabra food’, in reference to the sweet and prickly cactus fruit, sabra, which has come to mean any Jew born on Israeli territory, ironically it is also a commonplace Palestinian backyard fruit used for fencing.

Krantz, a reform rabbi, was making sense of the absence of Palestinian tangible and intangible heritage in the Israeli narrative. ‘Years later when I came to the Palestinian side I discovered otherwise. It took time for me to realise that this was just another aspect of the Israeli hegemony in Palestine and its denial of Palestinian heritage, history, culture, cuisine and people.’

The mere idea of one land for two people is anathema to Zionist ideology. Following the Nakba of 1948 the land, emptied of its inhabitants, was soon occupied by new residents. From 1948 to 1953, almost all new Jewish settlements were established on refugees’ property. The Palestinian cataclysmic catastrophe in 1948 marked the settlers’ colonial conquest of land and the displacement of its owners, a dual act of erasure and appropriation. Citing ‘reasons of State’, Israel’s first premier Minister David Ben Gurion appointed the ‘Negev Names Committee’ to remove Arabic names from the map. By 1951, the Jewish National Fund’s ‘Naming Committee’ had assigned 200 new names. But it did not stop with the destruction of the Palestinian landscape and the recreation of a new geography. The Zionist appropriation of Palestine as the national homeland for the Jews and the exclusion of the indigenous Palestinian Arabs encompassed innumerable cultural elements including cuisine. In this context, the ‘hummos wars’ is not about petty claims and counterclaims; Israel’s obsession with hummos is about more than usurping Palestinian tangible and intangible heritage. Rather, it is symptomatic of the Israeli denial of the Palestinians as people with legitimate rights and a historical connection deeply rooted in Palestine.

Hummos is the Arabic word for ‘chickpea’ and its history spans the vast regions of the Mediterranean from India to the Arab countries dating back to ancient Babylonian civilization, but finding a single place and time of origin has evaded historians. Today, hummos is central to Turkish, Lebanese, Palestinian, Syrian and Egyptian cuisines, just to name a few. Part of the reason for the mystery is semantic. Hummos only means ‘chickpeas’ in Arabic. What Westerners think of as hummos is actually called ‘hummos bi tehinah’. Its name suggests the two necessary ingredients of the dish: pureed chickpeas and sesame-seed paste, tehinah. Both culinary elements are major constitutive elements of ‘Levantine’ cuisine; a region that includes Syria proper, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan.

Hummos recipes have been recorded in thirteenth century cookbooks. Shihab el-Deen Ahmad el-Hanafi, an Egyptian author, described hummos in his book ‘Description of Common Food and the Flower of Elegant Dishes’.

In his cook book, Shihab el Deen described hummos el Sham, the hummos of Greater Syria as being sold in a vessel by street vendors. The addition of tehinah to hummos was an eighteenth century innovation. Tehinah-based sauces are common in Middle Eastern cuisine and when blended with mashed chickpeas to create the well-known breakfast dish ‘hummos bi tehinah’, this delicacy adds a festive quality to Friday breakfasts at home and features prominently in the daily menu during the holy month of Ramadan. Hummos as chickpeas is a ubiquitous staple in the Palestinian cuisine. Qidreh, the traditional festive meal of Hebron, Gaza and Jerusalem, brings chickpeas and cumin spice together to create this delicious mutton and rice speciality.

Chickpeas are commonplace to such an extent that they have become synonymous with the concept of the minimum basic staple. The folk perception of the nil Palestinian culture mobilizes the mundane chickpeas metaphorically. Describing an outgoing individual who recounts that all he/ she sees or hears without reserve, the saying runs ‘He cannot leave quiet a single chickpea in his stomach’ (Ma turkud humseh fi batnoh). Another popular saying describing the total loss and waste of effort in an unsuccessful transaction is: ‘He left the mawlid (the feast) without eating a single chickpea.’ (tile' min el mawlid bala hummos.) Mundane, small in size and commonplace chickpeas have become synonymous with insignificance.

Chickpeas are closely associated with the rich tapestry of Palestinian heritage. As early as middle March sour green almonds and hamleh, fresh green sweet chickpeas, are among the first harbingers of warmer weather, marking the end of winter. Whiling away the afternoon in village courtyards, eating lightly toasted fresh chickpeas warm out of the oven, is a common spring ritual.

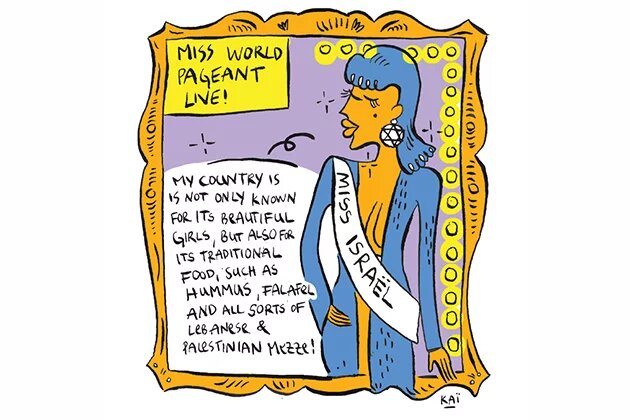

Cross-cultural exchange and cultural appropriation underlie different attitudes to other cultures. Pizzas, hamburgers, schnitzel, crepes and waffles have become popular fast food among Palestinians and indeed most cultures. No one would deny the Italian, American, Austrian, French or Belgian origin of these dishes. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one of colonial cultural appropriation, ethnic transfer and denial. The appropriation of Palestinian hummos by the Israelis and its promotion as indigenous Israeli sabra food within the context of occupation and ethnic cleansing of Palestine suppresses Palestinian social cultural identity and its deep roots in historical Palestine. In the decades following the establishment of the State of Israel on the ruins of Palestine, various elements of the indigenous culture have been targeted for appropriation: falafel, knafeh (traditional Palestinian sweet), sahlab (Palestinian drink) and, of course, hummos. Israel has claimed them all as its own: falafel is the ‘national snack’, while hummos, according to Israeli food writer Janna Gur, is ‘a religion’.

Since the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 and for the first two decades its people did not eat local Palestinian food; they came from all over the world and did not have a traditional food in common. As Vered, an Israeli chef says, ‘They stuck to their old habits.’ He goes on to explain. ‘It's also a political issue. If I eat Palestinian food, in a way, I acknowledge that they exist, that there are other people here who have food of their own.’ By the late 1950s, the Israeli army started serving hummos in mess halls. Since the basic ingredients, chickpeas and tehinah, do not break the Jewish laws of kashrut the Palestinian dish fits into any meal without breaking any dietary rules. Soon the ordinary Israeli came to know hummos as an everyday food and with time, hummos bi tehinah became common food for Israelis and was adopted as sabra fast food. As the local fare became more familiar to the Israeli immigrants from Europe, hummos became hip, something young people enjoyed eating. ‘Hummus became appropriated as the food of the new sabra’, explains Dafna Hirsch, an Israeli sociologist. ‘In Israel, hummus is considered a masculine dish,’ says Hirsch. ‘It's a kind of masculine ritual to go with a group of men to the hummusiya (fast food restaurant) and eat hummus, wiping with these large circular gestures.’

The Israelis have conquered the land, forcibly evicted the Palestinians and appropriated Arab heritage. Recognition and denial underlie the patronising attitude in which Palestinian Arabs have been eradicated from the landscape and the appropriation of hummos is just one more way of excluding Palestinians from the narrative of Palestine; it is another frontier in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. A conflict that is symptomatic of the Palestinian struggle for recognition as legitimate heirs to Palestine's tangible and intangible heritage. Hummus and Hummos bi tehinah debunk the Zionist myth of ‘a people with no land to a land with no people’; a myth in which the Palestinian presence is necessarily ignored.