What has happened to the transnational visions so characteristic for leftist movements? A number of political movements and ideological formations in the Middle East were concerned with ways in which to overcome borders. While Pan-Arbism, essentially a nationalist movement, was focusing on lifting geographic borders, socialist and communist movements scrutinized the social and economic borders within societies and contemplated overcoming class structures and confessional or ethnical divisions. Hanaa Edwar, member of the Iraqi Communist Party and the Iraqi Women’s League, joined the Iraqi Peshmerga in 1985 and spoke to us about the dream of overcoming all borders.

In the 1970s, I was living in (East-) Berlin as the Iraqi Women’s League representative at the Secretariat of the Women’s International Democratic Federation. The plan had been for me to return to Iraq in 1978, but that was just as Saddam Hussein’s Baath party began its anti-democratic campaign, closing the offices of the communists, arresting many of our friends and comrades and executing dozens of young communists and democrats. So it was decided I should stay and watch what happened. In 1981, I spent my vacation in Beirut attending military training run by the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP). I returned to Berlin to wait for the moment I could return to Baghdad and join the Peshmerga (the armed resistance movement against Saddam Hussein’s dictatorial regime). However, after four years I decided enough was enough, I couldn’t stay any longer in Berlin and I returned to Baghdad.

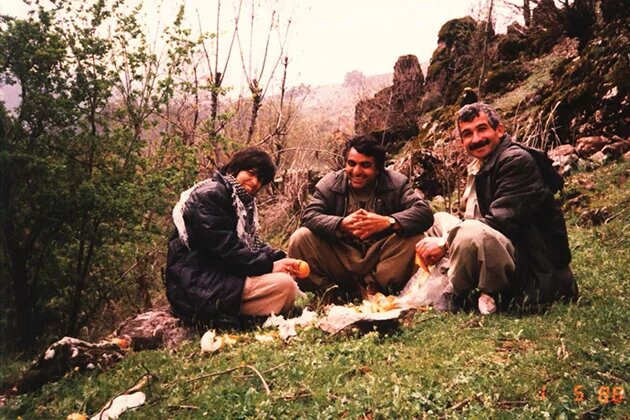

It was August 1982 when I returned to Damascus to continue my work with the Iraqi Women’s League. At that time I was a member of the Iraqi Communist party (ICP) and looking forward to joining my comrades in the resistance movement. This was a significant moment: women being accepted as Peshmerga fighters under the banner of (ICP). In October 1985 I attended the fourth Congress of the ICP in the mountains of Kurdistan; we numbered over 120. After the congress I stayed and joined the Peshmerga ranks, what we called “Ansar”, which had resumed its activities in 1979.

My nom de guerre was Nada. I stayed in the area of Khwakork, located in the triangle of borders between Turkey, Iraq and Iran, the base for a number of party politicians, as well as the headquarters of the ICP media, broadcasting and newspapers. As the representative for women’s issues I joined the political leaders of the party. We maintained contact with our sisters working inside Iraq under Saddam’s regime as well as the Nasseerat – female fighters – in Kurdistan. I had been given a Kalashnikov as well as a small pistol containing just five bullets. In our base, we numbered forty people, about twelve of them were women; the numbers changed depending on missions and people moving to different areas. Alongside us, about 10 minutes walk away, was the ICP broadcasting base where a number of young female journalists were working. I was astonished by the number of Iraqis with different social backgrounds who came from different provinces, ethnicities and religions: Arabs, Christians, Ezidis, Kurds, Mandaean, and Turkmens; we didn’t feel different we were working as one. Many had had a higher education: PhDs specialising in physics, philosophy, or the arts … Many came from Western countries or had graduated from the Soviet Union. They had escaped from Iraq after 1978 and gone to Algeria, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen then returned to join the armed struggle against the dictatorial regime, to build a democratic Iraq and grant dignity, freedom and a decent life for its people.

The Vision of Dignity and the Fight for Freedom

Most of the women who joined the Nasseerat were unmarried at the time. They were very young and willing to participate in the armed struggle under extremely harsh conditions. They had been assigned a variety of duties, working in telecommunications, the media, nursing and other everyday duties; a small number also fought. Amongst the party’s leadership in the mountains, there was one female comrade, Bushra Perto, a member of the ICP’s Central Committee. She was with her husband, who was also a member of the ICP Political Bureau and both spent several years in the Peshmerga; she lives now in London.

Our base was in a remote area. There were no markets, no social life, we were completely isolated and transistor radios were our main link with the outside world. From time-to-time we received letters and books through the party’s channel. We lived in very primitive conditions; men and women lived separately in shared rooms built from dust and sometimes in tents. The winters were cold, with heavy snow and rain but the sense of camaraderie and the stoves kept us warm. We took our meals together; usually three of us shared one dish. The food was very limited especially in winter: yogurt, cheese, lentils, chickpeas or a bean dish with rice. Sometimes we had honey, eggs and meat maybe once or twice a month. I don’t like meat, but many of my comrades looked forward to eating it and would join me so they could eat my share. We also had delicious freshly baked bread in the morning and at midday. Everyone, except the leaders and elderly people, had to take cook twice a month and prepare three meals for everybody in the base.

It was not an easy time for me. I am from Basra, a geographically flat area and relatively warm in winter. It found it hard to climb hills and mountains and to adapt myself to this new, primitive environment. I had difficulty raking wet wood to prepare breakfast for my comrade; it was also hard job for male newcomers to cut wood. However, I enjoyed the lovely colours of the landscape around us, the way it changed in the mornings, afternoons, evenings; throughout the seasons. During my guard duties in the evening or at night, the bright stars and the still of the dark fascinated me, a silence that was only broken by the swish of trees or the whistling of the icy, cold wind.

We were mostly isolated from other people but when people did visit, especially the women, it was good. They looked at us with astonishment: ‘These women, what are they doing in this remote area?’ - they had met Peshmerga men before but not female Peshmerga. With time, we were able to establish good relations, teaching them about hygiene, how to improve their living conditions and we also raised some awareness of women’s rights.

During this time, some couples got married both in our base and at another nearby. We celebrated the wedding and built them a special room. We made gifts from very simple things; like taking empty cans and painting them to look like vases, and we collected flowers.

In the summer of 1986, I remember one guy suffering from severe pain in his abdomen. We were lucky to have a surgeon with us who diagnosed an appendicitis and he needed an operation. But, how? The doctor decided to operate outdoors but after midnight to avoid contamination from dust and insects and using a local anaesthetic. We were all worried. We organized the space very simply and I volunteered to help, reassuring the patient when he felt pain during the operation. It was a remarkable achievement. After a week, our comrade regained his health and resumed his activities.

Bridging Isolation

Living in an isolated space with other people 24/7 was not easy but I don’t remember any major problems. It was like a prison, but open air and of our own choice. We used the time to read, work and debate. We had wonderful times. I remember we celebrated a week of theatre and it was so wonderful, absolutely amazing! We performed a number of plays in the evenings, followed by discussions and music. Of course, we always celebrated International Women’s Day and other festivities. These young fighters were honest and ambitious and tolerated these primitive conditions as a result of their devotion and commitment despite being deprived of many basic requirements for years.

One day in June 1986 we were moving from our area, the Soran (the countryside of Erbil) to the Bahdinan area (Dohukk province), that’s high up in the mountains where the hawks are. We were passing through very dangerous areas with Iraqi army check points and had to go across a small river to cross the Turkish border; while crossing the stormy water one of the men almost drowned but another was able to save him. I remember we had to walk for more than four nights, passing through villages and staying overnight in different people’s homes. We saw the ruins of villages destroyed by Saddam Hussein’s campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kurdistan, and we met people who had been displaced, some of them more than once. At the same time we had happy moments when we entered a small town, walked on a paved road and sat in a café and drank tea! That was a great pleasure for us!

We walked for many hours. Even when you’re tired, you have to follow the others and just keep on walking. We had few animals to ride on and I was not used to walking in mountainous area. I found it so difficult when we had to climb a mountain, so sometimes they got me a donkey to ride on. But I did enjoy swimming in the cold mountain rivers with other Nasseerat in the group.

After three weeks, we returned to our base but one comrade, Mona Lisa, extended her stay. In September 1986, while passing through the Turkish region, the Turkish army fired at them and she was hit, got an infection and died. The comrades couldn’t bring her body home and it was a huge loss for us. Originally from Nasiriya province she had been a wonderful young activist who had devoted herself to this struggle and to women’s rights.

I would like to mention other members of our Naseerat who infiltrated Iraq on party missions. They were hiding with their families and we lost some of them; I remember Zainab, Um Dhikra and Um Lina, one committed suicide to avoid arrest and the other two were caught by security forces and executed.

Turning the Weapons against the Opposition: Saddam Hussein’s Regime after the End of the War with Iran

In our group, there were some people from Iran who belonged to Fedaii Khalq and the TUDEH party, leftists. They were a wonderful group of men and women and we felt united in the face of a common cause. We enjoyed cultural and art sessions in the evenings and one of their girls married one of our comrades. When the Iranian troops entered the Iraqi territories, the party leadership decided to move them to the Bahdinan area for their safety and security. Unfortunately, one man, called Abo Ali, insisted on staying with us; he was so committed and funny but was shot by an Iraqi soldier during our comrades’ withdrawal from the base in July 1988. I was so sad to lose him. He had been a close friend to me and other Nasseerat. He had been away from his family for about five years and was so looking forward to meeting the small son he had left behind in Iran. Some of my comrades gave birth in this situation and it was wonderful to have these babies around and to hear a child’s voice after so long.

Chemical Warfare

In 1987, Saddam Hussein began his chemical attacks on areas of Kurdistan. I usually read through the telegrammes and messages received from other places and people were terrified of this fierce campaign. We received a delegation from Halabja who talked about the tragic situation they endured during and after the chemical bombardment of their town on 16 and 17 March 1988. In June of the same year, an Iraqi chemical raid was launched on the ICP’s base in Bahdinan, which I had visited a year before. It was horrible. Many comrades suffered from acute respiratory illnesses and chronic skin diseases and some lost their sight for several months. We were on high alert. Meetings were organized to explain the composition of the chemical weapons, its effects and how to recognize and avoid its threats during the raid. We had to be ready, at any moment, to run. Everyone carried a small bag ready containing what was needed in case of an attack; it was a very difficult time. During my time in the mountains, I witnessed Turkish and Iraqi fighter planes scanning and sometimes attacking our areas. We always had to be on alert.

Of the three years I spent in the mountains, the hardest was 1988. On 18 July, we heard Khomeini’s statement that he would ‘drink the poison’ to end the war with Iraq, which meant he had accepted the ceasefire between Iran and Iraq. We realised that the Iraqi army would turn its weapons against us, against all resistance movements, and they did so immediately.

Adios to Arms

We had to retreat from our base in Perbinan, walking in the heat, staying in the open for 2 – 3 days, and then moving to another. We received news of violent raids by the Iraqi army against the rest of our comrades who had stayed in Perbinan and Khwakork and against other Peshmerga forces. I was so sad and so angry; I was heartbroken. It was a pivotal moment and then I heard a rumour that a decision had been made by the leadership of the party to withdraw the Nasseerat, the sick and the elderly from the mountains. I was so emotional during the discussions about our retreat and withdrawal from Kurdistan and as an expression of my anger I washed my hair in a small river in front of everyone.

I remember the day when we, a small group of Nasseerat, were sitting in the tent feeling tearful and despondent and a member of the party leadership came to tell us about the decision to leave Kurdistan. We all expressed our dismay and refused to go, he tried to console us with encouraging words but there was nothing for it, we had to leave and soon!

The next day, six or seven Nasseerat and I left with our guide. It was so painful to say goodbye to our comrades. We walked for several hours and then the guide asked us to change out of our Khaki uniforms and into the village dresses he had brought for us. Most of us had not worn this kind of dress before and thought we looked funny; it made us laugh and tease each other, which lifted our spirits. We spent a chilly, dark night in the open trying to sleep close to each other to keep warm and when we woke up in the morning we were surrounded by sheep and goats.

There was no problem crossing the Iranian border illegally. We stayed with Kurdish families and it was so pleasant for us to take a bath in a public, Iranian bathroom. This marked the resumption of civilian life. Later on, I was separated from my friends and moved to the city of Naqadeh. After two days I heard the ceasefire between Iran and Iraq had started; it was 8 August 1988. One week later, I took the bus to Tehran accompanied by members of the family that I had been living with. My departure from Tehran went smoothly and within a week I had arrived in Damascus.

Other Nasseerat who didn’t have valid passports had to take a risk and cross the Iranian borders with the Soviet Union illegally; it was an adventurous, long journey. The majority of Nasseerat are scattered across several countries, mostly in the West, in Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands... Only a few are still in Iraq. They are married and have families, many of them have continued with their studies and settled into their new homeland but always remember fondly the warmth and love of the days of armed struggle.

Years later an organization called the League of Anssar Movement was formed which made it possible for old comrades to meet periodically. On some occasions special events were organized for the female fighters to come together and revive old friendships. Comrade Ali Rafiq, a filmmaker who spent years in the Anssar movement, made a special documentary about the experience of female fighters in Iraq titled: “AL-NASSEERAT”.

I am not saying this experience was ideal. But it is a fact that the ICP was a pioneer in involving women in armed struggle. Unfortunately little is spoken about it and I think we didn’t really give it much publicity. Even as we’ve been speaking it is clear that you thought the Peshmerga was Kurdish. In fact, the number of Kurdish women who joined the movement was small because they were able to stay at home and work in their cities.

Still the Same Dream

Remembering the old days, thirty years on, I still have the same hopes and dreams that we had then, a passionate attachment to meaningful struggle against injustice and oppression and the impetus to fight for freedom, dignity and equality.

I want to stress that ICP has always represented an inclusive image of the Iraqi people, and I am proud that I was a member of this party from early on in my life. I learned a lot of lessons: patience, living and working together on a community basis, caring for others and building intimate relations. Even to this day I continue to be in touch with some of my comrades.

In the light of the difficult situation the Iraqi people are facing today, I feel gratitude towards those who sacrificed their life to pave the way for others to fight with the confidence and determination to turn their dreams into reality through peaceful protest. I think joining the armed struggle has empowered women and proved that, in the face of difficulty, women can be trusted to act responsibly.

Based on our experience, both past and present, we must lobby for more leadership positions for women in order to break the patriarchal mentality and the totalitarian authority that believes in the marginalization and subordination of women.

---

Written by Dr. Bente Scheller.