Since the end of the Lebanese Civil war in 1990, public spaces in Lebanon, and Beirut in particular, have largely been assimilated into private ones in the name of post-war ‘reconstruction’. Here, I explore how cycling initiatives could empower a re-negotiation of space from private to public.

Mohammad al-Homsi is a 62-year old Syrian man who cycles fifty kilometres a day to work in Lebanon. There are no cycle lanes and he has to share the country’s notoriously dangerous roads with the cars, buses and lorries that have made them so.[i]

Despite being an exceptional cyclist, al-Homsi was Syria’s cycling champion in 1976, he has been hurt several times on his way to work. In 2017, in an interview with AJ+ Arabic he recounted how a lorry had hit him leaving him badly injured: and when lorries aren’t ploughing into him there are countless potholes and piles of rubbish to navigate. [ii]

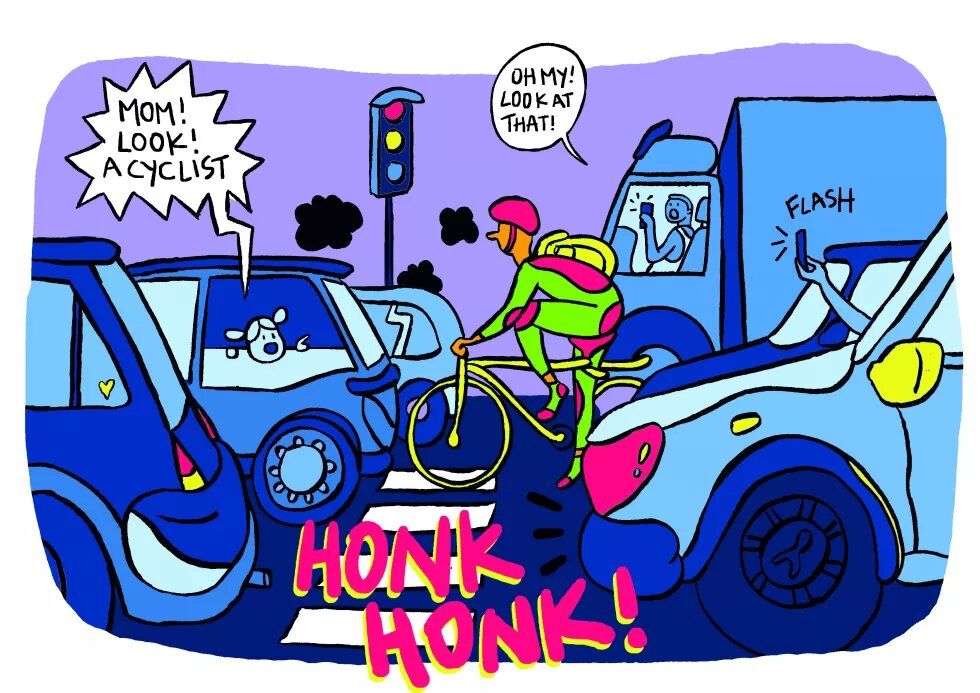

Tales such as al-Homsi’s are common among Lebanon’s small community of cyclists. I remember when I took up cycling while I was living in Beirut between 2010 and 2013 my friends and family wondered whether I had lost my mind and, in retrospect, I probably had. At this time cycling initiatives were still in their infancy and just like al-Homsi, every day I faced the danger of lorries driving erratically oblivious to the cyclists around them, ‘service’ taxis competing for custom and frustrated commuters raging at the wheel.

It would be an understatement to say Lebanon is not cycling-friendly and encouraging real change is taking far longer than hoped due to the lack of cycle lanes and road safety more broadly. The country’s car-centric infrastructure encourages traffic jams, wide urban highways and complicated interchanges and accidents are common. According to Internal Security Forces statistics between January and November 2017, 3,140 accidents were reported leaving 441 people dead and 4,179 injured.[iii]

Yet, thanks to many more cycling initiatives, some are hopeful that this is set to change in the near future. Take for example the ‘Bike to Work 2018’ initiative,[iv] which saw over 1,000 people ‘interested’ on Facebook on April 25, 2018. The concept was simple: two groups, ‘The Chain Effect’[v] and ‘Live Love Beirut’,[vi] with the support of several other bike shops as well as ‘participating cafés’, provided free bicycles and helmets available at a number of sites for people to use to travel to and from work or university. The Chain Effect has also been recruiting volunteers to paint the city with pro-cycling graffiti.[vii] In addition there is the Cycling Circle[viii] which organises group tours on bikes and owns a ‘bike café’[ix] which it describes as ‘an engaging bicycle shop and coffeehouse featuring a selection of bikes and accessories with an on-site repair service’. Revealingly, its co-founder, Karim Sokhn, told CityLab that ‘before the civil war in Lebanon, biking used to be for everyone. The police were on bicycles, the postal service, all the social classes’.[x]

As I will show, cycling in Beirut, in its negotiation of space, is an act of defiance. Indeed Sokhn has touched upon a subject that many people in Lebanon understand to be true, namely that increasing the number of people cycling everyday is an act of solidarity that signals the potential for change in Lebanon. While this may sound like an odd claim, in recent years many scholars have pointed out how sectarianism, widely perceived to be both catastrophic and inevitable, is far from natural, and is in fact reproduced on a daily basis through existing service infrastructures such as electricity, educational and social work facilities, credit services, and mobility infrastructures as Joanne Randa Nucho writes, ‘For my interlocutors in Lebanon infrastructure and service provision were topics of daily debate and concern and were directly interwoven with an apparently totally different topic, the notion of a sectarian community.’[xi]

The fifteen years of civil war destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure and public services were degraded. The post-war era was defined by a reconstruction largely executed under the logic of neoliberalism, public infrastructure fell into disuse and public spaces, once the symbols of a cosmopolitan capital, were almost entirely privatised. Contrary to popular belief, not all of this began after the 1975-1990 war. Indeed, Beirut’s tramways were decommissioned in the 1960s ‘to make room for more automobiles’.[xii] The country’s beloved trains, were largely abandoned or destroyed during the war and the last train ran in 1994. Adorned with a banner reading ‘the train of peace’, its demise symbolised the end of the pre-war era and the beginning of the post-war. The iconic trains[xiii]of the pre-war era elicit nostalgia[xiv] in the minds of many, and a sense of permanent loss to younger generations, unfamiliar with that period. While it is undoubtedly the case that Lebanon’s so-called ‘golden age’ (the 1950s and 1960s) is heavily romanticised, I can’t help but wonder what life would be like in Lebanon today if we still had an accessible and reliable means of transportation connecting the country’s different regions.

As an illustration of how important alternatives to cars, buses and lorries are, let us look at the 47-minute documentary by Al Jazeera on Lebanon's Harley-Davidson bikers.[xv] Its promotion hints[xvi]at the inherently political message that this group puts forward. Militiamen during the war, often on opposing sides, they are now united by their love of biking. Although somewhat of a cliché, it is no doubt the case that these men associate their motorbikes with a new way of experiencing their country, very different to the country of checkpoints, snipers and decreasingly mixed neighbourhoods of their youth. As two of the bikers tell us, shortly after the war bikers from East Beirut showed those from West Beirut around, and those from West Beirut returned the favour. The ease with which bikers can stop and communicate with one another is one that proponents of cycling, in addition to the many health benefits, hope to promote.

Today’s Beirut often feels like a grey monstrosity where cars and buses rule, as its depiction in Ely Dagher's short film Waves ’98 reminds us.[xvii] There are few spaces for pedestrians, and even pavements are converted into car parks. Cyclists, have only one prototype cycle lane[xviii] that cars regularly drive along and the number of cars on the country’s roads show no signs of decreasing. [xix]

This is why talking about bicycles in Beirut is ultimately a discussion about a basic right to freedom of movement. It is about how a city’s residents see one another. Endless congestions contribute to a feeling of unease already present in a population haunted by a violent past and uncertain future. Being stuck in traffic has become a metaphor for the Lebanese condition, just as the 2015 waste crisis that launched the ‘You Stink’ movement became a metaphor for widespread government corruption.

And how could it not? The lack of alternatives means that countless people spend hours every day getting from one place to another in the smallest recognised country on the entire mainland Asian continent. My daily trips to the American University of Beirut often took me nearly two hours despite my village being a mere twenty kilometres from the university. I calculated that in a year I spent a whole month in my car. It was only later, when I moved to the UK, that I realised what a difference to my life it made being able to walk and cycle, use the metro and train, which we do not have in Lebanon, as well as having reliable buses. As often as I could I found myself wandering through parks or just walking for hours at a time in an attempt to catch up on all those months lost driving around Beirut.

My story is not unique. Those of us who have travelled outside of Lebanon cannot help but feel especially frustrated by the lack of alternatives in our country. Frustration then leads to anxiety and a widespread sense of claustrophobia. It is as though our country is hostile to our very existence, invading our spaces at every opportunity. Needless to say, this feeling is itself the result of nearly three decades of a post-war status quo built without consideration for the people inhabiting its spaces.

While something as mundane as cycling would certainly not feature as one of the most pressing issues plaguing Lebanon today, I would argue that the mundane is in desperate shortage in a country relentlessly intent on squeezing out most of its population with what's left only available for the lucky few able to afford it. For cycling to happen on a large scale, national and local authorities would have to invest in appropriate infrastructures, that would enable residents of a city to feel they belong again. It may not solve everything, but it's a decent start.

[i] See: https://www.facebook.com/ajplusarabi/videos/415525815638649/ Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[ii] See: https://www.facebook.com/ajplusarabi/videos/415525815638649/ Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[iii] See: https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/en/originals/2018/03/lebanon-beirut-world-bank-congestion-new-transportation-bus.amp.html Accessed: 17 September 2018

[iv] See: https://www.facebook.com/events/419509558477448/ Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[v] See: https://www.facebook.com/TheChainEffect/ Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[vi] See: http://livelove.org/about Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[vii] Larsson, N. (2017) “‘Beirut is more beautiful by bike’: street art reinvents a notorious city – in pictures.’ The Guardian Newspaper. Thursday 15 June 2017. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2017/jun/15/beirut-bike-street-art-chain-effect-in-pictures Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[viii] See: https://www.facebook.com/cyclingcircleLB Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[ix] See: https://www.facebook.com/pg/cyclingcircleLB/services/ Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[x] See: https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2017/09/beirut-tries-to-get-back-on-the-bike/540681/ Accessed: 17 September 2018

[xi] Nucho, Joanne, R. (2016) Everyday Sectarianism in Urban Lebanon: Infrastructures, Public Services, and Power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. See further details at: https://press.princeton.edu/titles/10884.html

[xii] See: https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2017/09/beirut-tries-to-get-back-on-the-bike/540681/ Accessed: 17 September 2018

[xiii] See, ‘Lebanon Hopes to Revive Train Lines’ on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnWHc9H4iTE Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[xiv] See, ‘Rare Footage of Tripoli Lebanon Train Station 1970’ on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kMNx_5hv3u8 Accessed: 14 September 208.

[xv] See, ‘Lebanon: Fighters to Bikers - Al Jazeera World’ on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wvwBw1XqCXk&vl=en Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[xvi] See, ‘Meet Lebanon's Harley-Davidson bikers, who put aside their differences through their love for biking’ available at: https://twitter.com/AlJazeera_World/status/963721347971993601 Accessed: 14 September 2018.

[xvii] See Ely Dagher's short film Waves ’98 available at: https://vimeo.com/252441577 Accessed 14 September 2018.

[xviii] See, ‘First Bike Lane Prototype introduced in #Beirut’ available at: http://blogbaladi.com/first-bike-lane-prototype-introduced-in-beirut/ Accessed 14 September 2018.

[xix] See: https://impakter.com/traffic-crisis-lebanon-entrepreneurs-rise-challenge Accessed 17 September 2018.